Life Through Black Eyes

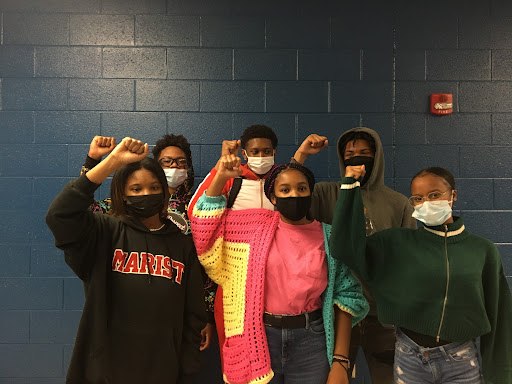

Left to right. Front row: Kayla Gibbs, Kaylee Powell, Samantha McLeod Jones. Second Row: DJ Mays, Bryson Fleming, Dante Craft. Photo courtesy of Natalie Brown.

December 16, 2021

This article can also be found in the exclusive December print edition focused on Chamblee’s identity. Copies of the newspaper are being distributed at lunch Thursday, December 16.

When I was in sixth grade, I was really close friends with this white girl. We spent a lot of time together and goofed off in class. We had social studies together and just like every other social studies class, my teacher talked about slavery.

At the end of the year, my teacher gave us the option to choose between a group project and a test for our final. Knowing my inability to focus would’ve impaired me on the final, I chose to do the group project with my then friend and two other Black girls. For this project we had to make an informational video. We could either act the information out or simply inform the listener about our topic and the effect it had had on our lives. The white girl in our group immediately exclaimed that we should do our video about slavery; we could be slaves, she could be the slave owner, and she could use her belt to whip us.

Sitting there in shock, I didn’t know what to do. I was caught totally off guard and thought it was a ridiculous thing to say. I told a lot of my Black friends, who then said they had all her say racist statements, but she always got away with it. After a bit of deliberation, I decided to go to my counselor about this whole situation. My friends said that even though she had been caught saying these things, there was a very small chance anything would happen and that I shouldn’t get my hopes up. I wish I had listened.

When I went to report my issues, I was told to go to the white guidance counselor instead of the Black one because she was the one designated for my last name. I told her what happened and she seemed partially empathetic but almost as if she didn’t completely understand what was wrong. She brought the girl into the office and told her what she had said was wrong. The girl responded that “slavery was a good thing and slaves should’ve been grateful because it gave them a place to eat and sleep!” Once again, I looked at her in shock and asked where she got this information from. She cited “Gone with the Wind” as her reliable resource. My counselor told her that that wasn’t true because she had gone to South Africa and it’s very pretty there. She then made me leave the room to have a conversation with the girl. I came back in and was given a half-hearted apology. The girl then started crying and was told to go back to class. The counselor looked at me and said “she had been through enough.”

The girl switched groups and we made our video about the Mayans. She continued to say phrases like “I don’t like Black music [rap]” and that “I know how to talk properly [talking without African-American Vernacular English.]” She was never punished for these things, yet wearing a durag or leggings would get us in trouble all of the time.

This situation taught me a few things: I can’t rely on the school counselors, white tears are stronger than Black pain, and this was just something I was going to have to put up with for the rest of my life.

I can’t say that was my first experience with racism, because for a good portion of my life I was oblivious to it, but once those words left her mouth, I started to notice things. Sometimes I would go on walks and watch people cross the road to avoid me and my dad or I’d deal with an old lady coming to yank at my “exotic” hair. Usually, these encounters were with people I didn’t know, but every once in a while, it was someone who was a friend. Sophomore year, I was called an “Oreo” – a Black person who is perceived as acting white, and therefore Black on the outside and white on the inside like an Oreo cookie – multiple times, often by white people but also Black people. Generally, these were “jokes” but they often caused me to feel like I didn’t “act Black enough” The “jokes” kept going and instead of talking to my counselor about it, I stuffed the feelings of anger inside and sat with other people during lunch because I don’t feel like I can talk to the counselors. If they didn’t help me when I had such a big issue, why would they help me with such a small issue? Constantly being ignored when we speak up is a major reason why so many Black students feel helpless at times. When we speak up people don’t listen until it’s a white person speaking on our behalf, until a video goes viral, or until a Black person dies.

Sometimes racism isn’t blatant. It doesn’t always require someone shouting out slurs or beating people up for their race. Sometimes it’s the little things that only the person it’s directed at will notice. It can be very brief and subtle. These are known as microaggressions.

“I’ve seen a lot of microaggressions,” said senior Kayla Gibbs (’22). “Especially [when] Black young girls wear [their] hair in styles they like. [They are] are often being asked if it’s real or get comments about the way we speak. There are so many microaggressions in this school that it came to the point of being normalized by students because they create jokes as well.”

Black girls’ hair is often held up to scrutiny. It’s either too nappy, dirty, ugly, or fake. No matter how our hair is done, someone has something to say about it. This also means that a lot of people want to experience our hair for themselves.

“One of the most common microaggressions I have faced are comments about my hair and the unsolicited touching of my hair. I feel some students do this purposely because they know this makes us feel uncomfortable,” said alum Evelyn Raphael (’21).

When students encounter racially charged verbal attacks, we don’t all react the same. Sometimes we just look in amazement of the sheer ignorance displayed, maybe we sit with our mouths agape, and sometimes we confront the situation. Either way, there are multiple different reactions and none are inherently wrong. During senior Bryson Fleming’s (’22) encounter with racism at Chamblee he was in too much shock to know how to respond.

“I remember last year this white older kid, he was like ‘Black people [were] slaves for reasons you wouldn’t understand,’ and no one said anything about it,” said Fleming. “Me and my friends was like, ‘What the?’”

Senior Trey Middleton (’22) has a different approach. He prefers to confront people when he knows they’re wrong.

“It was my first year in high school and I was in the gym with my friend and we had to get lined up to do our attendance so we were in alphabetical order. This guy who was behind my friend, he was being rude to her and I don’t know how this argument started but all the sudden you hear ‘I don’t respect you or your kind,’ and then we started asking him what he meant by that,” said Middleton.

Some students have racist experiences from both students and teachers ranging from using terms such as “Blacks” and “colored” to making blatantly racist statements. Middleton had one such experience.

“My family is Jamaican, so I brought a traditional Jamaican breakfast called porridge. I brought it to my first period so I could eat it in the morning, and everyone was eating in that class, it wasn’t just me. [My teacher] saw what I had and it looks like blended oats, like a heap of wheat. She looked at it like it was garbage and said, ‘Please don’t ever bring that to my class again.’ And I knew it wasn’t because I was eating but [rather] what I was eating and that kind of threw me off a little bit,” said Middleton.

During the summer of 2020, several white students from Chamblee were called out for saying the n-word in their Instagram or Snapchat stories. Students were outraged and we saw two new Instagram pages pop up that allowed for students to express their own stories. The pages were @bipocofchamblee and @Blackatchamblee. Even the Chamblee Facebook page had something to say. On June 2, 2020, a Chamblee alum wrote,

“Greetings, I am Chadwich Smith, a 2013 alum of Chamblee Charter High School. As many have expressed already I am outraged at the racist behaviors of several white students who thought it was appropriate to use the words ‘N-er’ and ‘N-a’ on camera.

“I recommend that in order to move forward, Chamblee’s administration hold these students accountable by requiring that they stand before the a school wide assembly expressing in detail why their use of the N-word as white people in unacceptable. “In addition to a school wide assembly,” Smith continued, “Chamblee needs to host race-based affinity spaces to address this topic in depth amongst the students. The purpose of these affinity spaces is not to coddle the egos of white students but to get to the root of racism, white supremacy, and white privilege in the classroom and beyond. Additionally, these spaces can be considered safe/brave spaces for Black students and students of color to express the microaggressions and overt acts of racism they experience every day.

“There are many qualified alumni who are able to help facilitate both the assemble and affinity spaces,” Smith stated. “They must be paid for their labor, for we know that one of the pillars of white supremacy is the unpaid labor of Black people and people of color.”

The students caught saying the n-word were never punished and the school has yet to address this issue. I’ve heard rumors of a vague email being sent out, but I have never seen it with my own eyes. Many Black students were forced to live with this knowledge that their peers were so eager to say the n-word or make their own sacrifices to avoid people.

“I actually played lacrosse with one of the girls who was caught saying the n-word. After seeing the video, I had hoped the lacrosse team would release a statement but it never happened. After seeing the stance the team took on this issue, I decided that I no longer wanted to play lacrosse,” said Raphael.

After the summer of 2020 some students were hoping coming back to school would be a little bit more progressive but within two weeks of school that ideal was shattered.

“We were doing this discussion in anatomy and this [Black] kid comes over and he showed me his paper because we had to write down […] what we thought about the discussion. And on this paper, it was talking about ‘Black girls are like ghetto and they stink’. And he thought it was the funniest thing,” said senior Tae Jones (‘22), who is new to Chamblee.

This paper was brought to the teacher’s attention and also caught traction throughout the senior class, but once again the student was never punished.

Later on, this same student was part of a presentation in classes where they had to present an MLK speech. The student and one of his partners, not Black, repeatedly said “negro.” When a student voiced their opinion about how hard Black people have to work to be seen on the same level as white people, the other student responded, “That’s tough!” That caused the two boys to erupt with laughter while making many others in the room feel very uncomfortable.

“We had a white teacher. He’s pretty cool, but it seems like I’m just the angriest person out of everybody. Maybe I’m just super sensitive to stuff like that but it didn’t seem like really anybody cared. It felt [invalidating],” said Jones. “I guess I can’t expect people to be as angry as I am.”

Police Brutality

During Thanksgiving break, I was driving myself and my brother to my dad’s house. A trip that only takes about 5 minutes through Murphey Candler felt like an eternity. As I drove across the river, I saw two police cars. One turned left and another turned right and followed me. My heart was beating faster than ever. I started thinking ‘where’s all my information’, ‘are my hands in the right spot,’ ‘are my lights on,’ ‘don’t forget to stop for 3 seconds, maybe more,’ ‘is my brother buckled in, will my brother be able to call our parents, will he be able to record on my phone,’ ‘is everything ok?’ Then he turned left and I realized that for those 2 minutes, I never truly breathed out. I had gone completely silent and to make it worse, I’m not even sure if my brother understood what was happening. I was scared shitless… of the police.

“Don’t make sudden movements.”

“Don’t talk back.”

“Don’t have the radio up too loud.”

“Don’t guess what you did wrong, let them tell you.”

“Do keep your hands on the wheels.”

“Do talk through every step.”

“Try to be in a public well-lit place, if safe.”

“Try to record everything, if safe.”

“Try to Facetime me, if safe.”

“Remember your goal is to get home safely.”

These are the common rules I was taught by my father. The rules that people of color had to come up with to stay safe from the police. Stay safe from the police. The same people who are supposed to serve and protect us, we now must stay safe from. We can’t make sudden movements because “they get scared.” We can’t talk back because “we’re resisting arrest.” And we can’t have the radio up too loud because “we’re being disorderly.”

The recent murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Daunte Wright, Rayshard Brooks, Daniel Prude, and Casey Goodson, Jr. by police have taken a toll. The knowledge that we people of color are always one mistake or action away from death is not very pleasant.

“The [deaths] put a large toll on my mental health and view on the law enforcement system in America. The actions that I have seen are simply sick and heinous. At times, I even questioned the police/security at our school. [For example] there was a time that I witnessed a Black student having their book bag checked thoroughly and barely checked the white kid’s bag, and it was during the time that some of the police came to our school to check our bags in the morning,” said Gibbs. “I understand they needed to make sure the students didn’t bring any weapons and such but sometimes it’s like they were choosing who looks more “threatening” or not.”

Every day a task that white people can do almost carefree is considered nerve-wracking for many Black people.

“[George Floyd’s death] affected me mentally because I’m driving and worry about if I’m going to be pulled over for doing this or doing that. So basically whenever I’m driving I have my hood on in the car, I don’t look Black [and] I don’t look white. I don’t want people to see me when I’m at a stop sign. I always try to stay incognito when I’m in the car,” said Middleton.

Driving isn’t the only time Black students must be careful. It’s pretty much ingrained into our minds that we can’t do as much as white people can and get the same repercussions.

“The list [of actions I have to think twice about] is quite long but some of the most common ones include: going to parties, hanging out with people who smoke, hanging out after dark, and wearing certain pieces of clothing,” said Raphael.

For many Chamblee students, this isn’t something new. It’s a reality that we must face every time we turn on our cars or walk down the street, that it may be our last action. But for some, this is the first time they are being made aware of just how unjust the system is.

Sometimes we feel like those stories are distant and could never possibly happen to us or someone we love, but the reality is that it’s everywhere; you just have to notice it. My parents have been through it and so have many others.

“A few months ago my mother was pulled over by the police while I was in the passenger seat and when I saw the flashing lights my heart immediately stopped. I immediately pulled out the camera and I made sure the license and registration was easily accessible. Luckily, we were just stopped because we had a temporary plate instead of a permanent plate. The issue was resolved within five minutes, but to this day, it still gives me chills,” said Raphael.

When being pulled over a lot of people think you have to stop where you are and pull off to the side, but in general, a person can typically drive until they feel “safe.” The upside of this is that people of color can drive to a public place where there are witnesses. The downside is that you may be seen as fleeing the scene.

“I’d rather be choked out in public,” said Middleton. “If [the police] want to kill me, at least kill me with the cameras on.”

The fact that any teenager has to think like that is horrible. What’s worse is that way too many have to agree with this sentiment because we are constantly one toy away from death (Tamir Rice), one Skittle’s pack away from being shot (Trayvon Martin), one locked door from being shot in our sleep (Breonna Taylor), and one $20 bill away from being kneeled and slowly choked to death (George Floyd). So can you blame us?

The “Correct” response

To say there is a correct response to racism would be kind of ludicrous. America was built on racism, a system put in place by those in power centered around racist ideas to put people of different races down in society. Sometimes it’s difficult to charter the correct path, but there are ways around that. For example, when a student of color tells you something you said or did offended them – you stop saying or doing that thing.

“As I have grown up I have learned that racism is ingrained in almost every aspect of life. I am not necessarily afraid of these things but I do approach them with caution. Some of these things include: corporate America, sundown towns, and people who fly their confederate flags with pride,” said Raphael

Continue to protest and post. BLM is a movement, not a trend or aesthetic. Too many times a movement like this picks up traction for a few weeks, maybe months, and then all of the sudden it’s gone. Something as serious as this needs to trend until it’s fixed.

“I think it’s important for us to continue to fight for our community and a change for our people. At the same time though, we need to be responsive to the injustices being committed against other groups of color. We must produce a united front if we ever want to see a change in this systematically racist system,” said Raphael.

Here are a few of Raphael’s favorite hashtags:

#BlackLivesMatter

#StopAsianHate

#FamiliesBelongTogether

#StopICE

#NoHumanIsIllegal

#StopIslamophobia

#NotATerrorist

Call people out, even if it is your friend. Over the summer of 2020 when the white students were caught saying the n-word, their friends would generally laugh at them. Those people in the video never really got in trouble at the school. Sometimes it’s like the school forgets that seeing those videos have an impact on Black Chamblee. It’s on the students to hold each other accountable.

“Some of these students were people I knew and spoke to before so I was actually very shocked, and the fact that they didn’t get in trouble or called out makes me very upset because some of these students made racist comments before and no one bothered to say anything,” said Gibbs.

A lot of times people get away with their racist “jokes” because others laugh out of awkwardness. This is seen as validation to keep going. Rather than laughing, call them out. Let them know that you are not okay with what they say. By staying silent you are actively part of the problem.

“Most of the time, when these situations happen and the student gets called out. [The person affected is] labeled as “sensitive” or “someone who can’t take a joke” even if it’s with their own friends,” said Gibbs.

If you are white, know your voice has an impact and use that to help us. If you constantly see your Black friend or coworker being talked over by someone who doesn’t do it to any other race, speak up because there is strength in numbers.

Don’t victim blame. This should be obvious but clearly, it’s not to some people. George Floyd didn’t deserve to die because he may have been a “thug.” Breonna Taylor didn’t deserve to die because she was dating a “thug.” Neither of these are justification for murder.

Learn. Even though I am here explaining a few students’ perspectives to you, I won’t always be able to answer your questions. There are also many times where other Black people don’t want to answer your questions as well, not because we don’t want to help, but rather sometimes there are things you need to learn for yourself. There are many online sources that you can learn from.

https://www.Blackpast.org/research-guides-websites/

AuntKaren0 on TikTok

“[It would help if white students] educated themselves and treated Black people normally and equally. Don’t abuse their allyship within the Black lives movement,” said Gibbs.

Understand we are tired. I just don’t have it in me anymore, I don’t have the energy to preach justice for [insert the next Black person to be murdered]. I don’t have the energy to hear about another person my age dying, I don’t have the energy to walk down the street and fear for my life every time I see a police car and I sure as hell don’t have the energy to deal with microaggression in the building I’m supposed to feel “safe.”

“The constant exposure to police brutality on a daily basis has really taken a toll on my mental health. Not only is it on the news but now it’s also on social media which just causes me to shut down sometimes and not want to interact with anyone,” said Raphael.