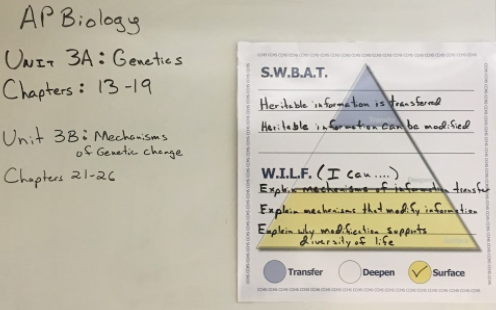

WILF and SWBAT: for some students at Chamblee Charter High School, those acronyms are foreign and meaningless. However, teachers and some students know that the newly-introduced WILF and SWBAT teaching method actually stands for “What I’m Looking For” and “Students Will Be Able To.”

“[SWBAT] is just supposed to be for what a student is supposed to be able to do that day with whatever lesson is going on,” said English teacher Jennifer Andriano. “And then WILF is What I’m Looking For. And that just means what kind of product the students will be able to produce, or what they will know by the end of the lesson.”

The WILF and SWBAT teaching method was presented to teachers and students this school year by Principal Rebecca Braaten and the new Chamblee High School administration.

“[Teachers] were introduced to [WILF and SWBAT] at the beginning of the semester and told that we should start implementing it in the class as soon as we could,” said Andriano. “Some teachers got to it right away, some teachers haven’t. I made a beautiful board, and haven’t always filled it in, but occasionally I do. I think it’s been something that wasn’t told ‘you have to do it day one,’ but that over the course of the semester you really should start, and that we should also start explaining it to the students.”

Science teacher Deann Peterson uses WILF and SWBAT to explain to students what they are currently learning.

“For example, in AP Environmental Science, where we talk about dissolved oxygen in aquatic systems, [an example SWBAT would be to] be able to explain to me the effect of dissolved oxygen in an aquatic system,” said Peterson. “A WILF for that would be how does dissolved oxygen vary with temperature, how does dissolved oxygen vary with the amount of algae in the water. Those would be the WILFs, those are the specifics, but the big idea of WILF and SWBAT is knowing what you’re supposed to be able to explain [at the end of a class period.]”

For Family and Computer Science teacher Carrie Dickey, WILF and SWBAT are simply new acronyms for an already used teaching concept.

“Basically, I am already doing what [WILF and SWBAT] do,” said Dickey. “So it wasn’t anything that was unusual for me, because I already do it, and I have told the students about it, but they know my teaching style. So, it’s fine to be up, but I’m already doing that without having [the new acronyms].”

Dickey uses her refined teaching skills to teach effectively to a wide variety of types of learners.

“It’s just natural that I teach to all phases of learning,” said Dickey. “I teach the visual learner, the kinetic learner, the naturalistic learner. See, I do that, so [the WILF and SWBAT are] just up there.”

Junior Hamida Tanha has noticed little to no impact from the introduction of WILF and SWBAT on her daily classroom experience. In fact, when asked what she thought WILF stood for, Tahan proposed “What I Learned From” and “What I Expect… Something.” During random lunchroom interviews, some other suggestions included “Why I Love Food,” “Women’s Intervention Life Funding,” and “Water In Land Forever.”

“[WILF and SWBAT are] like, in every classroom, but I don’t know what [teachers] want, the teachers haven’t explained anything,” said Tanha. “I’m thinking it’s like a standard that all the teachers are expecting from us, or something. None of the teachers have discussed it, so it’s not beneficial.”

Like Tanha, Andriano recognizes some of the drawbacks of WILF and SWBAT.

“I do think that if sometimes all [teachers] do is stick an acronym up there that student’s aren’t aware of what it means, than it doesn’t mean anything,” said Andriano. “So, WILF can be easily turned into other things that already have an acronym for them and are inappropriate, and SWBAT just sounds silly.”

Unfortunately, creating a daily WILF and SWBAT can be time costly and inefficient for teachers like Andriano.

“In theory, they’re supposed to be useful,” said Andriano. “In reality, it takes a lot of time to come up with a different one each and every day or every two days and in a lot of classes, especially for English, students will be able to do more than just one thing. It’s not like in math, okay you’ll be able to simplify this equation. [For example,] today we’re doing an essay where [students are] doing an outline and have to come up with a thesis statement, and so the SWBAT is long. And WILF, I’m looking for a lot of things. For me, it’s not as simple, in English it’s not as simple as some other classes.”

Peterson recognizes that if used incorrectly, WILF and SWBAT are meaningless to students.

“If a teacher is just putting them up there to ‘pass inspection’, as they say, then they’re not functional,” said Peterson. “I try to do everything to make it functional for my students, to help explain it. I can think of myself as student going, ‘what the heck was that lecture about today? I don’t know, I’m done, 50 minutes is up, I’ll walk out the door.’ Whereas here, it’s like, ‘oh yeah, I can explain what dissolved oxygen does in an ecosystem now,’ kind of thing.”