Your donation will support the student journalists of Chamblee High School Blue & Gold. Your contribution will allow us to print editions of our work and cover our annual website hosting costs. Currently, we are working to fund four print editions for this school year. Help us reach our goal!

An Analysis of Chamblee’s “Cheating Culture”

May 9, 2019

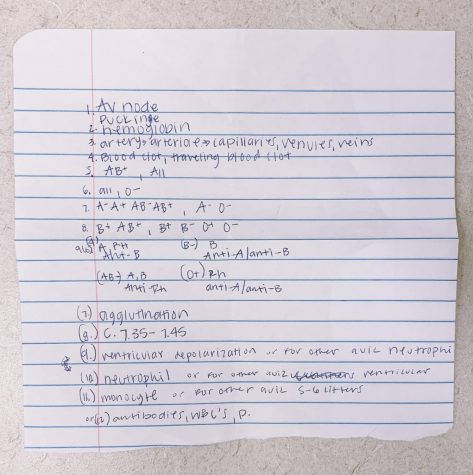

During the aftermath of a quiz earlier this week, anatomy teacher Leila Warren found a small piece of paper sitting on a desk in her classroom. Upon closer inspection, the paper was revealed to contain the answers to the quiz and was presumably used as a cheating device by one of her students.

“Every teacher who finds a cheat sheet or a student actually cheating is furious inside,” said Warren this week. “The nerve of students to just not even care enough to study […] is like a smack in your face. It’s rampant here at Chamblee. Students don’t actually want to work for their grades; they just want to get a grade.”

Warren’s statement seems to ring true, so much so that cheating is seen as a cornerstone of Chamblee’s academic sector.

A cheat sheet found by anatomy teacher Leila Warren revealing answers to multiple quizzes.

“Cheating is Chamblee culture,” said one Chamblee Charter High School student when asked to comment on the prevalence of academic dishonesty in the school’s environment.

A statement as drastic as it is worrying, Chamblee’s so-called “cheating culture” raises a lot of questions. Is it a byproduct of the school’s academic-oriented reputation, or encouraged by external pressure? Does it come from a flaw in work ethic and character? And most of all, is Chamblee’s cheating culture as inevitable as the majority says it is?

What further seals this sentiment of “inevitable cheating” are the relatively ineffective measures taken to prevent academic dishonesty. At Chamblee Charter High School specifically, attempts to stop cheating tend to focus on why students should not cheat rather than analyzing what influences students to cheat. But in the past, attempting to make cheaters understand how their actions are unethical has only resulted in mockery, as seen with Chamblee’s “X Out Cheating” movement.

By taking the perspectives of Chamblee’s teachers, students, and chronic cheaters into account, more light can be shed on the cheating at Chamblee, along with the particular mindset that it stems from. Breaking down the act of cheating in this way offers insight into the issue’s causes and effects, along with its possible solutions and tentative inevitability.

The Effects of Cheating in the Classroom: A Teacher Perspective

From the words of Chamblee’s teachers, the main problem with academic dishonesty does not lie in its moral wrongness, but in its creation of an undesirable learning environment.

“Cheating diminishes the whole system and affects every kid, even those who never cheat,” said language arts teacher James Demer. “Now, I have to run my class in a way to make sure you don’t cheat, rather than running it in a way to help you learn.”

Social studies teacher Jennifer Tinnell finds that the effects of cheating include a dysfunctional learning environment and a tarnished school reputation.

“A school is like a family. It takes all parts of a family for it to work the right way,” said Tinnell. “If we want Chamblee to be a school of integrity and a school that earns and deserves all the accolades that we get, then we need students to be on board with that as well.”

Language arts teacher Amy Branca can attest to Tinnell and Demer’s words. For her, cheating causes inconvenience in the classroom and supports a toxic environment in schools.

“It changes the focus from trying to get people to love learning the way that we do. […] We [become teachers] because we have a passion for what we teach, and we want to share that,” said Branca. “If I’m more worried about people trying to figure out how they’re not going to do the assignments they’re given, then I have to spend my time creating six different reading check questions for every class and five different versions of the test instead of teaching.”

However, Branca says that cheating is more than just an inconvenience for teachers.

“[It] burns you out because instead of you and your class being a team, all working for the same goal, it becomes you against them,” said Branca. “They’re trying to game the system and you’re trying to stop them. It becomes a cat and mouse game. That’s not why anybody got into teaching.”

For many teachers, the act of cheating undermines their jobs and continuously breaks the trust between them and their students. It can also serve as an indication of character.

“It’s not just the matter of a grade. It’s about who you are,” said Branca. “You can always change your grade, but you can’t change your character. Once I find out that you cheated, that’s the end of my relationship [with you]. We may have to stay in this room together, and you may have to turn in work, and I may have to give you a grade, but we don’t have a relationship beyond that anymore.”

Amongst the teaching community, cheating is also associated with a poor work ethic.

“Life is all about choices. We always have a choice between right and wrong, taking the easy way out,” said Tinnell. “I wish [students] would have, first of all, more respect for themselves, more confidence in themselves that they can do it the right way, the hard way, the long way and not take shortcuts and not make poor choices.”

Chemistry teacher Kathryn Zuehlke says that the unethical character amongst the student body pertaining to cheating has led to a disillusionment with education as a whole.

“A couple of years ago, I had a class where I felt like I needed to take a shower after whenever that group of students walked out of the room,” said Zuehlke. “They were just so full of lies and sneaking and cheating and whatnot that I just felt dirty. I didn’t want to deal with them. […] If I had to deal with them all the time, I would be looking for a different job. Part of the reason why teachers don’t address [cheating] is, in terms of what makes [their] jobs miserable, dealing with cheating is way up at the top.”

Zuehlke also says that cheating often makes lying into a crutch for many students and that their dependence on it can lead to dangerous situations.

“There are studies that show that cheating is linked to mental health and just a sense of security,” said Zuehlke. “But honesty is a source of simplicity in power. […] If you’re not sticking skeletons in your closet that you don’t want people to find, they’re not going to fall out in opportune times. We’re seeing that with some of our politicians right now.”

Teachers also notice a problem with a student mentality that contributes to cheating.

“Students are too often obsessed with comparing themselves to others. This is very damaging to so many aspects of our school community,” said Demer. “I don’t know about other schools, but as a community, we should emphasize learning, and de-emphasize grades. I scold parents about this every year, but little changes.”

This mentality is especially associated with Chamblee’s magnet program, where students tend to focus more on their grades and academics, creating competition.

“The need for perfection is driving maybe some behaviors that could lead to cheating,” said Tinnell. “There’s no shame in a B. There’s no shame in a C. That probably is a lesson that a lot of kids from Chamblee could learn.”

Despite its association with academic performance, Branca maintains that cheating is widespread and not just limited to the competitive environment of the magnet program.

“I know there’s that old saying that magnet students know how to cheat better, but it’s not just magnet students. Their motivation is different,” said Branca. “This level of competition that you guys have created amongst yourselves, that the teachers try really hard to un-instill in you, that it’s all about the grade, that is frustrating. […] Magnet kids may be trying to get ahead and trying to get a better GPA, but general kids are [cheating] to just graduate high school.”

Why Cheaters Cheat: A Student Perspective

The students interviewed for the next three sections wish to remain anonymous. To ensure anonymity, names of famous Ancient Greeks have been randomly assigned to each interviewee. Students are in no way affiliated with the people of their assigned names.

In an ideological clash with the teacher perspective, Chamblee’s cheaters maintain that their academic dishonesty is attributed to a mentality that has been molded by external rather than internal factors. An intense pressure to succeed, coupled with a lack of time, motivation, and aptitude, is what students hold accountable for the inadvertent creation of Chamblee’s cheating culture.

One of the students that believes this is Aristotle, a well-experienced cheater.

“I cheated for every class. Every single class,” said Aristotle. “I ask for homework and copy it. I change up everything. […] After cheating for four years straight, it gets really easy. Especially at Chamblee, I feel like it’s very easy to cheat because everybody’s into cheating.”

And, Aristotle says, the reason why so many of Chamblee’s students are chronic cheaters is because of their fear of failure.

“Everyone’s mentality is ‘I need to pass, and if I don’t pass this, I’ll fail, so I have to resort to cheating,’” said Aristotle. “It’s not that I want to cheat. It’s that I have to. We don’t want to break [a teacher’s] trust just for fun. We’re not really intentionally doing this.”

There are other ways that students like Aristotle justify their cheating. For many students, cheating is often seen as a form of learning.

“I cheat by learning. I copy it, but I’m paying attention to what I’m doing so I know what I’m doing,” said Aristotle. “For math, I don’t think I’ve done one homework assignment this whole year, but my lowest test grade was an 88, and I didn’t cheat on that.”

Other justifications for cheating come from an issue with the class itself.

“Social studies classes have always been trouble for me. I cheat on those [tests] by writing down dates,” said Aristotle. “I’m terrible at social studies classes. I hate them, but I still have to take them. […] It’s something I’m not interested in, so I just cheat to pass the class because I don’t care about it, but it’s still a requirement.”

Meanwhile, Socrates, who doesn’t regularly cheat, says that he has just recently resorted to academic dishonesty because of the way a particular class of his is taught.

“The teacher gives us assignments that we have no idea how to do. [They] never taught us the material, and we don’t really have another option,” said Socrates. “We’re not just going to accept a failing grade because we don’t know how to do it. It feels like we’re forced into cheating for a decent grade.”

Efforts to talk to the teacher in question have been unsuccessful.

“People have approached [the teacher] about it before, but I don’t think there’s been any change,” said Socrates.

Unfortunately, this creates an even bigger problem for students in the class.

“I don’t think anyone is going to pass the exam. It is an AP class,” said Socrates. “We’re not learning through the cheating. […] It’s not ideal. Everyone does it [in that class]. I don’t think there’s a single person that doesn’t.”

Despite Socrates not being a seasoned cheater, he and his peers continue to accept it, harboring sympathy for those that choose to cheat regularly.

“It’s really just a student’s prerogative,” said Socrates. “I don’t view it as morally bad, per se. I just think it’s a choice. […] Some assignments really just aren’t worth your time. There are 24 hours in a day. You’re trying to organize your time between sports and clubs and grades, especially for straight-A students that are trying to go to really good schools.”

Plato, who tries to not make cheating a habit, fits Socrates’s description of a good student that cheats due to a lack of time.

“I don’t cheat often, but I cheat when I feel like I have to,” said Plato. “A lot of the times, for a lot of people that are taking higher-level classes, […] we get a lot put on us. A lot people do things outside of school, like dancing or theater or sports. We just don’t have the time to absorb every single piece of information for every single test.”

The Rise of Systematic Cheating

It seems that this widespread acceptance plays a part in encouraging academic dishonesty. Pythagoras, who has a past of cheating as an underclassman, says that cheating is so normalized in Chamblee’s community that it has become systematic.

“There is one grade in this school, and they have a system [for cheating]. They’re going to all succeed because no one wants to see their friends fail,” said Pythagoras. “It’s by your cliques and the people you know. I don’t know the smartest cliques, but I do have a friend that does know them. He gets the answers, and sends them my way. [When] someone needs them from me, I just pass them along.”

Hypatia, an observer of cheating in her own grade, can offer an insider’s knowledge into the workings of this system.

“It’s pretty organized. […] I’d say that 70% of people cheat,” said Hypatia. “Someone has started an Instagram account that’s basically just for answers to work for classes or tests, and there’s also a Snapchat about the same thing. To be on the Instagram, they have to approve you, so I guess that makes it secure.”

The system Hypatia describes is reinforced by a lack of repercussion.

“Teachers know, and they say, ‘Oh, we can find you,’ but nothing happens. People know that nothing will happen so they just keep doing it,” said Hypatia. “[On Instagram], they delete it after it’s been posted so they won’t get caught.”

Systematized cheating is also partly encouraged because it contributes to a “social hierarchy” within Chamblee.

“[The person that distributes the information] gets ‘clout’ from it, is what we say,” said Aristotle. “Everyone says, ‘Hey, this kid, he’s smart and he gives us the answers.’ And everyone tries to be friends with him to get the answers.”

Similarly, a cheating instance that once happened in Demer’s class was driven by an attempt to gain status.

“I once had two kids turn in the same essay. So I gave them both zeroes on the assignment, and they maintained their innocence until the end,” said Demer. “Turns out they’d both paid a kid to write their essay, and that kid gave them both the same one. […] The saddest part was that the author was hoping to be accepted by the ‘popular’ kids.”

Another effect of systematic cheating has been the creation of a “code of silence” among students, another reason why Chamblee’s cheating culture is not obvious at first glance.

“It’s throwing someone under the bus. It’s ratting someone out,” said Democritus, a student who does not cheat but still refuses to alert teachers about Chamblee’s cheating. “You don’t want to tell someone that somebody is cheating because it will ruin it for them, which will ruin it for you.”

Whether it goes by the name of narking, tattling, or now, snitching, turning a fellow peer in for cheating often leaves a stain on one’s reputation.

Scrawls on a desk written to use during an assessment.

“If you snitch on someone, you’re ruining your social life,” said Democritus. “This whole no-snitch thing is a really sensitive thing because people don’t want to ruin their own social lives by telling the truth.”

From an actual cheater, snitching is actually seen as a greater offense than cheating.

“Snitching, in my opinion, is terrible. You’re never going to catch me snitching on someone,” said Aristotle. “I would rather take the responsibility [of being caught cheating] than snitch. I think it’s worse than cheating.”

Moving Forward: A Student and Teacher Perspective

Despite the “anti-snitch” policy amongst students, teachers are not oblivious to academic dishonesty. Three years ago, social studies teacher Carolyn Fraser and other teachers formed the Academic Honesty Council as a response to cheating.

“It was a teacher initiative,” said Fraser. “We had found that the prevalence of cheating, whether it was copying homework or cheating on tests, was really up. We didn’t have a good way to address it. […] It left too much for teachers to handle on their own.”

In the past, the council also had a fairly active role in the classroom.

“We came up with this academic honor code that went through the [school] board, where we got it approved,” said Fraser. “At the beginning of every year during the first week of school, we would have teachers go through parts of it in every period and how they expect the students to live up to it.”

Starting this year, however, the council’s actions have been suppressed, which explains why some teachers and students are unaware of its existence.

“Unfortunately, this year, we were unable to do that because of the confusion in the beginning of the year,” said Fraser. “It just didn’t get done. Teachers are now asking for us to make sure that we don’t stop it. […] We were hesitant to start up the council this year because [of this].”

The council functions in a way that gives students some leeway. During the first infraction of cheating, when a teacher emails Fraser and the administrators, the student receives a zero on their assignment. When the student is caught twice, a trial is conducted.

“It is on the second infraction […] when we pull the student in,” said Fraser. “One time is understandable to a certain extent. […] Second time, there’s a pattern. We want to find out what are the problems that the student is facing, if they just don’t understand it, if they’re overloaded or stressed. We try to talk it out and be able to give the student a face to report to.”

Fraser says that a problem amongst students is that instead of speaking up, they immediately assume that they will not receive help from teachers and resort to cheating instead.

“We recommend that the students talk to their teachers if they’re overloaded. A lot of the teachers are willing to accomodate,” said Fraser. “If you have too many tests in a day or if you have family issues, most of us will accommodate you and give you a deadline delay, but you have to talk. You have to be your own advocate as a student.”

AP Psychology teacher Kurt Koeplin is one of the teachers who will grant students some leeway with test dates or deadlines in attempt to prevent cheating caused by stress.

“I’ll delay [a test] for any kid that says, ‘Oh, I had two other tests today. I had this project due tomorrow,’” said Koeplin. “I’ll adjust around [your] schedule, but all you have to do is come to me first. Don’t try to pull some shenanigans on a test.”

Like Koeplin, Branca is willing to do the same thing.

“If you [cheated], and I ask you about it and you say, ‘I got overwhelmed. I had too much to do. It’s my fault. I procrastinated. That’s why I cheated,’ I’ll say, ‘Okay, I get it. Let me help you organize your time better. Maybe I need to set smaller chunks of assignments so that you can do better,’” said Branca.

In order to take steps to prevent cheating, Plato says that many students are hoping for collective change.

“It’s going to take time because it’s not a change that’s going to happen overnight,” said Plato. “You have to break down why people are cheating […] and then the school has to think about if they can lessen the workload. It would have to be a whole effort. It’s not just going to be ‘Don’t cheat because it’s wrong,’ and we’re going to stop. That’s not working now, and it never has.”

Yet other students, especially the ones that regularly cheat, have already accepted Chamblee’s cheating culture as inevitable. Aristotle, who represents a good portion of Chamblee’s chronic cheaters, says that the only way to stop him would be to change the entire education system.

“Without a doubt, if grades did not matter as much as they did, I would stop cheating,” said Aristotle. “If it mattered more about teachers wanting to see how much you know, I would want to learn anything. There would be no point in cheating anymore. […] It’s about grades, and it will always be about grades.”

NeSmith Mary Alice • May 9, 2019 at 1:35 pm

Thank you for a great article that I will discuss with my 2 students as a family.