What Are You Doing in My Swamp: Protecting the Okefenokee

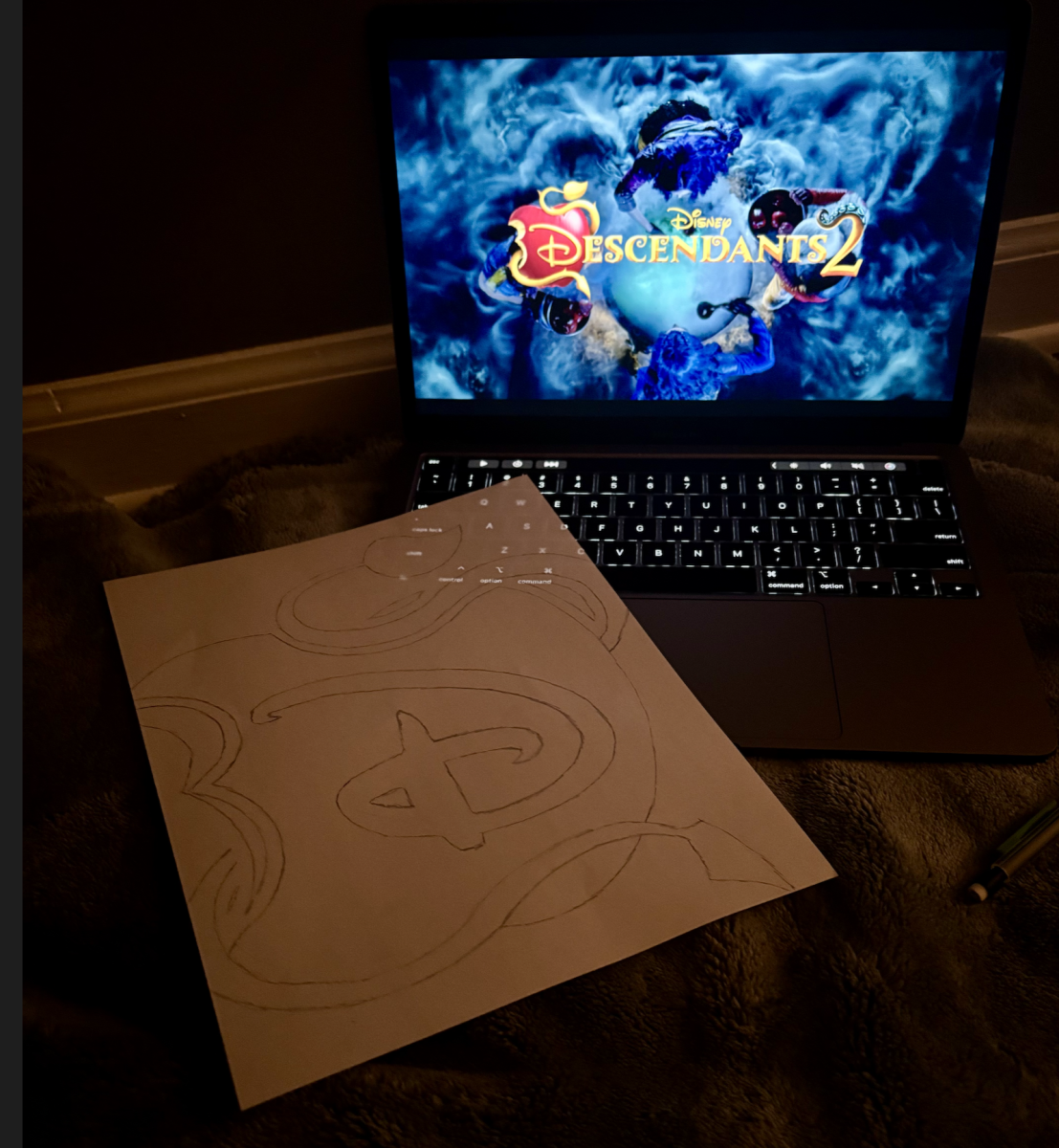

Photo courtesy of Michael Cowan

Troop 434 canoeing through the swamp.

September 9, 2019

From the Barrier Islands to the Appalachian Mountains, Georgia hosts a diverse array of ecosystems and natural wonders. With such a captivating landscape, you would think that somewhere within the 60,000 square miles of our state, there would be a national park, and yet there isn’t; in order to see a true national park, it requires a road trip, possibly even a cross country flight.

As someone who has travelled Georgia from north to south, it shocks me that nowhere here has achieved that coveted national park designation. I started pondering which locations were most suitable to become a national park, and there was an obvious answer: the Okefenokee Swamp. Located at the southern end of Georgia, the Okefenokee contains over 700 square miles of land, making it the largest blackwater swamp in the country. It is undoubtedly the most unique landmark in Georgia and the most realistic candidate for national park status.

A few years ago, I visited the swamp with my Boy Scout troop to do a multi-day canoeing trip through the dark waters. It truly is unlike anything you’ve seen before. The landscape is covered with pond cypress, all draped with Spanish moss, and beautiful lilies float atop the surface. Alligators poke their eyes out from the water and stared suspiciously at your canoe before darting below the dark waters (Our group started a game where we counted all of the alligators we saw, and we reached nearly 130). The water looked like solid obsidian, broken only by the touch of our oars. The mystic scenery and unique flora and fauna are unparalleled to anything else I’ve ever seen; it was almost like a koi pond with alligators instead of koi fish.

One of the many alligators spotted along the trip.

And it isn’t just the incredible natural landscape that makes the Okefenokee worthy of national park status. Designating the Okefenokee as a national park would bring light to an important issue that is happening right now that isn’t gaining much coverage. Twin Pines Minerals, a mining company from Birmingham, Alabama, is seeking a permit to mine for titanium and other metals along the southern edge of the swamp. Such strip mining could affect water levels and quality in the swamp itself, and could also disrupt minerals in the soil and water, which could negatively impact gopher tortoise and eastern indigo snake species in the swamp.

This mining situation echoes a 1997 controversy with DuPont mining company, which proposed a very similar plan. DuPont, however, was quickly shut down by then governor Zell Miller and Clinton-era Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt. Current leaders like Brian Kemp are saying nothing, and the fate of the Okefenokee remains undecided.

With national park status, the swamp could gain a lot more awareness for the Twin Pines mining issue and restrictions and limits for the company would likely become much stricter. So it isn’t just an arbitrary title; becoming the Okefenokee National Park could not only bring Georgia it’s first national park but also help preserve one of the greatest ecological sites in the country from dangerous mining.

Patricia Siedlewicz • Sep 12, 2019 at 5:08 pm

I really enjoyed this article. Its very well written and thoughtful. What steps need to be taken to bring your suggestion to fruition?

Tiramisu? If I knew, I would have made you make it for me this summer.

BTW You come from a long line of family members who have green thumbs, including John. Keep that family tradition up.