A Chamblee Student’s Guide to Protesting

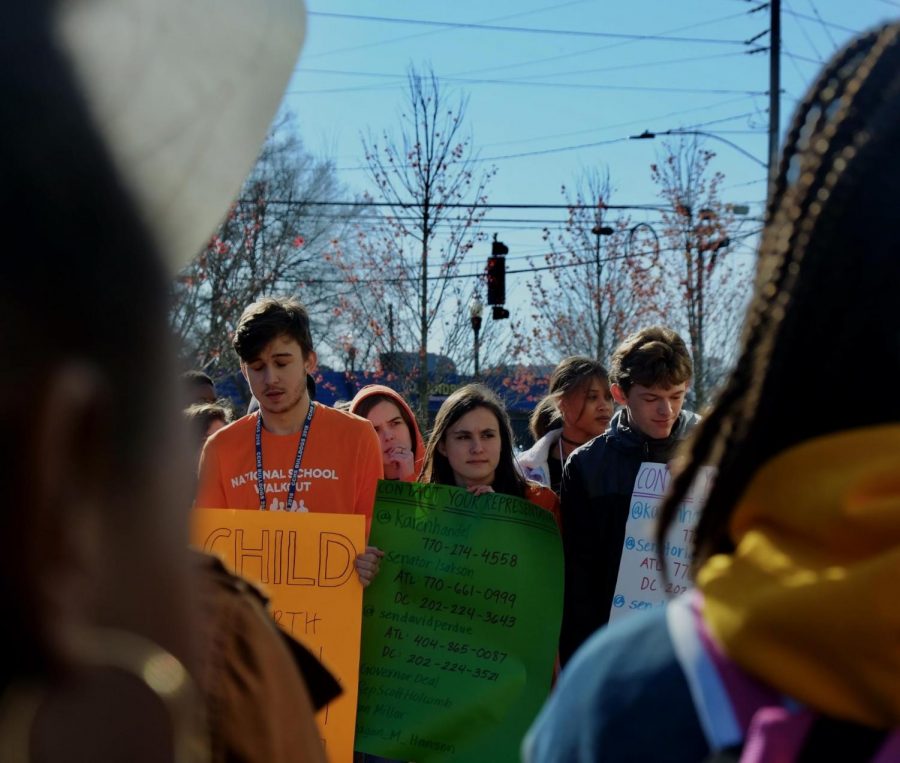

Photo courtesy of Iris Tsouris.

A group of Chamblee students attend a walkout protest.

December 6, 2019

Preface: The Relevance of Protesting

From my own observations as a high schooler, it is increasingly apparent that Generation Z—those born from the late 90s to early 2000s—has been tasked with correcting mistakes of the past.

As natives of the Internet, ‘Gen Z’ers were born during a digital age—an age where knowledge of climate change, discrimination and gun violence is as widespread as it is alarming. Plagued by problems trickling down from earlier generations’ shortcomings, Gen Z faces this adversity in solidarity. And as the youngest established generation, they also face an expectation to solve the aforementioned problems, ensuring a better future for themselves and for generations to come.

But with the majority of Gen Z being under 18 and not having yet secured the right to vote, the chance of change seems slim. The expectation that a group of teenagers can single-handedly reverse climate change is far too great to be realistic… allegedly.

That is precisely how protesting comes into play. Protected under the First Amendment, anyone, theoretically, has the ability to protest. And because of its accessibility, protesting has long been the voice of disenfranchised people, seen in Martin Luther King Jr.’s movement of civil disobedience in the 60s.

Additionally, protesting is effective because it garners attention; it is fueled by emotion, symbolizing a desperate outcry for change. Oftentimes, the press flocks to protests for coverage, and as a result, many protests go viral, where they receive even more support (as seen with the recent Hong Kong protests).

But more importantly, protesting is especially relevant to Gen Z. As a generation actively seeking out reform yet lacking the prowess to command it directly, protesting is an excellent way to start a conversation about change, even as an adolescent.

Your First Protest: Preparation, Posters and More

In May 2019, I attended the ‘Do Better Georgia’ march and experienced the power of protesting firsthand. A pro-choice march aimed at the recent Georgia Abortion Laws, the protest left me with a greater understanding of issues at hand, as well as greater knowledge of how to prepare for a protest. Below is a list I have compiled from the experience, along with the help of Amnesty International USA.

When protesting, never underestimate the power of a good poster. Chamblee junior Djuna Demer said when she attended the DC Women’s March following President Donald Trump’s inauguration, the most visible posters were the most successful.

“[Posters] have to be able to be understood from far away because there’s so many people,” said Demer. “My sister had one that said ‘Women’s rights are human rights,’ [and] I had one that said ‘45’ with an X over it because [Trump] is the 45th president.”

In general, a powerful poster includes a succinct yet bold message. Keep it brief, but do not stress about being original; oftentimes, the repetition and rallying behind one slogan can really drive a message home.

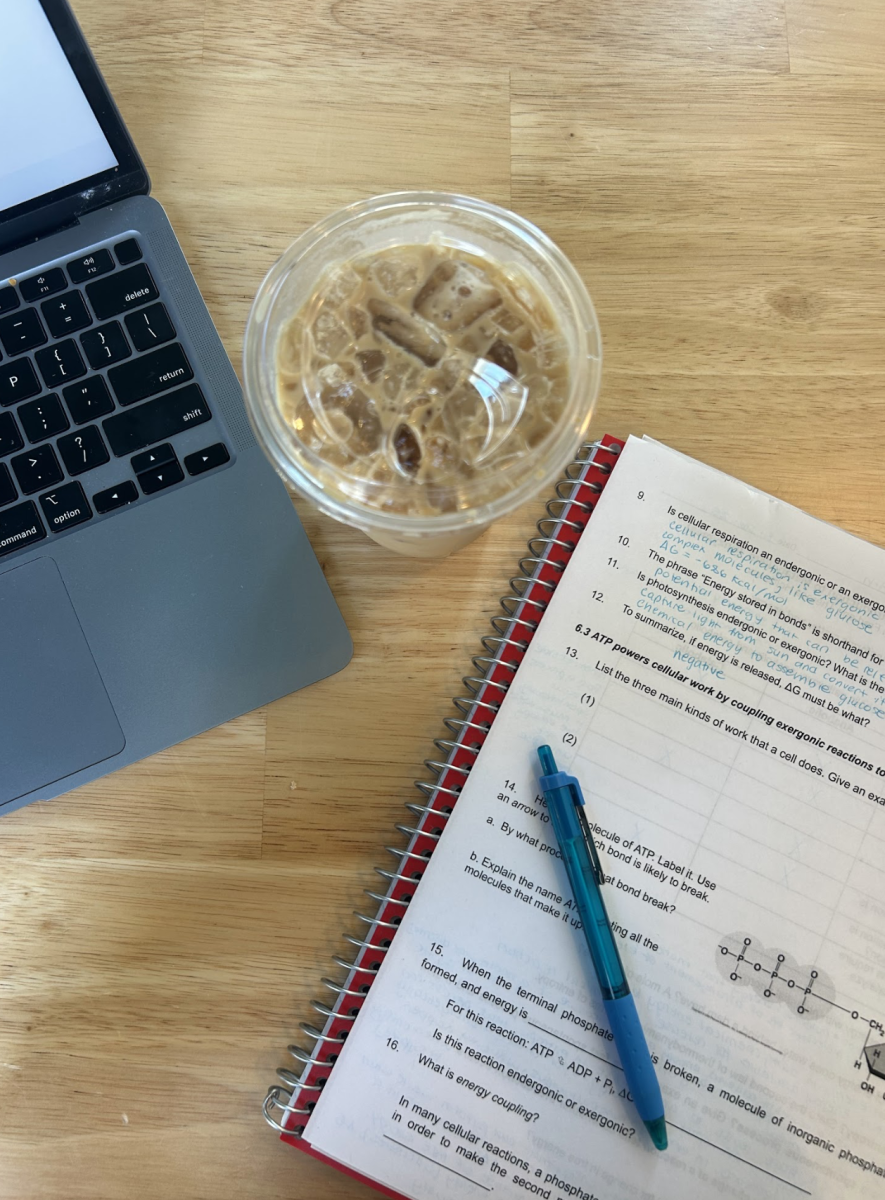

Junior Nicole Vaccaro during her freshman year, posing with her ‘March For Our Lives’ poster.

In this case, rhetoric is your best friend. Although frowned upon in political speeches, rhetoric in your poster assists greatly in making a dramatic, yet eye-catching statement. Do not be afraid to be controversial.

With that being said, controversy is not a requirement. In many instances, humor can go a long way. At the ‘Do Better Georgia’ protest, one of the more popular posters was one claiming that Georgia Governor Brian Kemp “wrote the final season of Game of Thrones,” a statement referencing the widely-regarded unsatisfactory conclusion to the HBO show.

My poster from the ‘Do Better Georgia’ march.

In preparation for the ‘Do Better Georgia’ protest, I drew a picture on my poster, which I strongly recommend doing. Art, often used as a medium to communicate ideas through, pairs incredibly well with political activism.

During the Protest: Knowing Your Rights

When protesting, one of the most crucial parts of staying safe is knowing your rights in the event of possible detainment. Demer, an avid protester, recalls an event where she was denied the right to protest at Chamblee High School.

“At Chamblee, the summer before [my sophomore year], there was a big meeting about the county and [Principal] Braaten,” said Demer. “I had made a bunch of posters, and I came in, and I was holding them, but I wasn’t holding them up because my plan was to stand at the back of the auditorium so I wasn’t blocking anyone so I couldn’t get in trouble for holding up these signs.”

Despite her plan, Demer still faced confrontation with the police.

“Three police officers approached me and they were like, ‘You can’t have those [posters],’ and I was like, ‘But my right to protest…’ and they were like, ‘You’ll be removed,’” said Demer. “I was like, ‘Okay, that doesn’t make sense, but I’ll take it.’ I’m not trying to get arrested for a thing about our principal.”

As it turns out, the police officers were not infringing on Demer’s First Amendment rights. Although schools like CCHS are publicly owned, they are not open-access, meaning that free speech can still be restricted on campus if deemed disruptive.

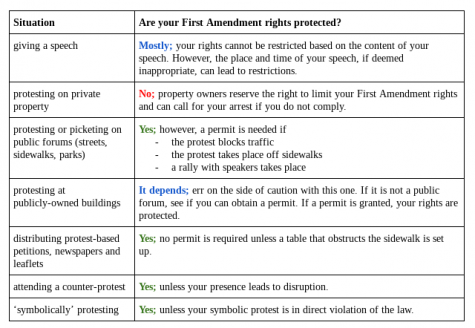

Protesting rights are further detailed in this guide from the American Civil Liberties Union. Because the guide is organized in paragraphs, an informational diagram is provided below.

Protesting in A School Environment

Because schools fall under the ‘protesting at publicly-owned buildings’ category in the diagram above, students that wish to conduct a protest during school hours should start with contacting the administration first.

Although schools can still suppress protests, Demer maintains that in a school environment, protesting has a place in preparing students for a future in professional activism.

“[School] is a good place for kids to learn their limits in protesting,” said Demer. “Like, how you should do it, how you should go about it professionally so you don’t get arrested or in trouble with anyone […]. Knowing those limits that you have will also help you if you go past your school and start protesting actual government.”

Former Student Body President Jake Busch (a senior at the time) leads a rally at Chamblee’s walkout.

In fact, there have been protests conducted at CCHS in the past, the most widespread being the National School Walkout. Current Student Body President Lucy Adelman played a role in bringing this movement to Chamblee’s doorstep in 2018—a protest made to combat gun violence and school shootings.

“First, I saw stuff on Instagram about a ‘National School Walkout,’ so I started doing research,” said Adelman. “I found out that it’s a national movement that started in the wake of the [Stoneman Douglas High School] shooting and that anyone can lead a walkout at their school.”

To plan the walkout, Adelman initially contacted the Chamblee administration.

“I sent an email to the principal asking if we could [conduct a Chamblee walkout], and she said yes. She told me to meet with her and bring a friend,” said Adelman. “I reached out to the Student Body President at the time, Jake Busch, and asked if he’d join me […]. Together we got administrative approval and had SGA working with us to make the walkouts a reality.”

Women’s Political Club President Tiffany McWilliams (a sophomore at the time) attends the Chamblee walkout.

And the walkouts were, in fact, a successful reality. Junior Megan Woo, who marched with me in the ‘Do Better Georgia’ protest and attended the walkouts as a freshman, noted that the National School Walkouts inspired her to engage in activism later on.

“It made me aware that high school students can be part of something [important],” Woo said.

Standing Your Ground While Protesting

Despite having uplifting qualities, attending a protest can also be mentally taxing, especially when faced with intense opposition. Demer, particularly, has been subject to this opposition multiple times.

“I’ve dealt with counter-protesters at Pride. They can get really aggressive and loud, and they’ll yell at you a lot,” said Demer. “The best thing that helps me is just remembering that they don’t understand your point of view.”

According to Demer, it takes a certain degree of empathy to stand strong in the face of aggressive counter-protesters.

“I get why they’re doing it and what they’re standing for, but it helps me to remember that I know what I’m doing is for my values and what they’re doing is for their values,” said Demer. “I don’t disrespect them, but I understand that one of us is being the bigger person.”

Even the Chamblee walkouts were not without opposition.

Blue & Gold editor-in-chief Ava Lewis (a sophomore at the time) holds her poster defiantly during the Chamblee walkout.

“There were people who did not support the walkouts,” said Adelman. “[But] because my heart was in it and because I knew I was leading for the right reasons, I could focus on standing up for what I thought was right rather than getting in arguments.”

Although Adelman strayed from conflict, her communication with counter-protesters actually had some positive effects.

“I did, however, have a couple of in-depth discussions with people who had different opinions than me. Although my opinions did not change, it always helps to hear other people’s way of thinking and hope that by having discussions, you’re just a little bit closer to a less divided world,” Adelman said.

But in the end, it boils down to having a strong purpose, along with the drive to fulfill it; fundamentally, the act of protesting has always, throughout history, been about correcting an existing injustice.

“To me, you cannot fully rally behind a cause without some level of passion. Your intentions have to be to make the world a better place and bring light to an issue important to you,” said Adelman. “We all disagree on some issues but what matters is that we are all trying to make the world a better place, and as long as we operate on that mindset, protests and civilized outrage are valid.”