The Artists Behind the Art: Exploring African-American Culture Through Art

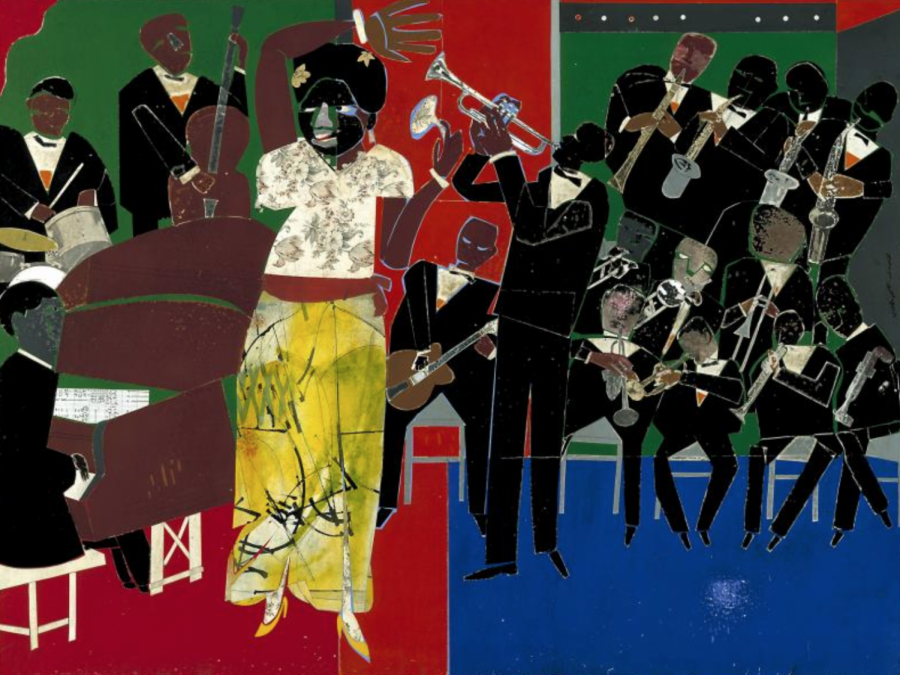

Courtesy of the Smithsonian Museum of American Art.

Empress of The Blues, by Romare Bearden, (1974).

February 28, 2020

“Black art has always existed. It just hasn’t been looked for in the right places.”

-Romare Bearden

I’m in love with visual art. I spend countless hours scrolling on my phone, pinning sketches to Pinterest or saving pieces to my camera roll despite the fact my attempts at drawing or painting have usually ended in a masterpiece of failure. Despite my refusal to sit down and finally practice — so I could actually improve my skills — I still admire it and dream of one day being able to create like that.

I’m also in love with my AP Literature class. Granted, I usually love any English or literature class I take, but this year has been nothing less than exceptional when looking at the vast collection of books we’ve read, the depth of our in-class conversations, and the enrichment we’ve gained from exploring the culture behind the things we read.

Ms. Keathley makes it a priority to expose us to so many different authors and stories, from reading The Bluest Eye in first semester to reading King Lear last month. One of the things I value the most about this class is the opportunity I have to sit back and listen to my classmates of color describe their experiences in discussions concerning racism and discrimination even in their experiences at Chamblee. I really value getting to hear these stories that are usually overlooked or undermined and realizing all I don’t know about the black community and have yet to learn.

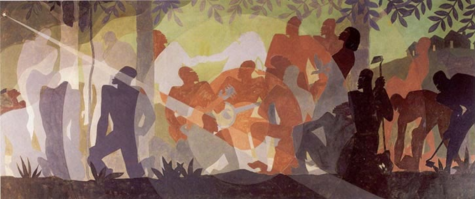

While doing a project introducing us to the world of the Harlem Renaissance in preparation to read Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison, we were told to choose a painting by Aaron Douglas and write a review on the piece. When first opening the page that showed all the different works of art, I realized I had seen these images before — in textbooks, on elementary school walls, on flyers — but never had made the connection or been told of who the artist really was.

I’ve obviously learned about countless white artists in the past, as well as many Hispanic or Latinx American artists in Spanish classes, but noticed a gap in the number of black artists I could name or describe. So I decided this month to explore the world of African American culture in a way I hadn’t before and began finding familiar artworks and finally connecting them to their artist.

This was one of the first pieces that caught my eye during the project in AP Lit. Aaron Douglas was a preeminent artist during the Harlem Renaissance, the same time period as Ellison’s novel. Many aspects of this piece stood out to me: the muted tones, the manipulation of light, the graphic silhouette style, and the concentric circles that make an appearance in many of Douglas’s pieces. The painting itself shows from right to left the tragedies that came with 20th Century black migration to the northern cities of the U.S — slave labor to the injustice after Reconstruction in a still divided country. The middle section showing the prominent music scene — very centralized in Harlem — is highlighted by the circles and persists through the suffering that enshrines it. Douglas originally intended to just pass through Harlem but decided to stay and develop his art, inspired by European Cubism and African art, and later became an editor of the monthly journal of the NAACP, The Crisis. His passion for art came from his admiration for his mother’s drawings.

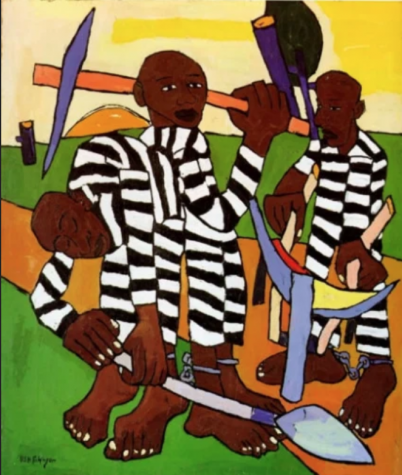

This piece by William Henry Johnson shows an important image in the history of African American struggle and brutal abuse in the United States, one that still persists today in many forms. Johnson probably was inspired either the men he saw growing up in South Carolina, or while he worked in the Works Progress Administration (WPA) where archivists preserved the stories of gangs like this one. The pervasive images of shackles and the obvious implication of unfair conditions, where one fall could bring down the entire group, sends chilling reminders of the experiences and continued experiences black people face in our country. His style evolving from realism to expressionism to a folk style, all beginning with an introduction to sketching by his teacher Louise Fordham Holmes, who included art in her curriculum.

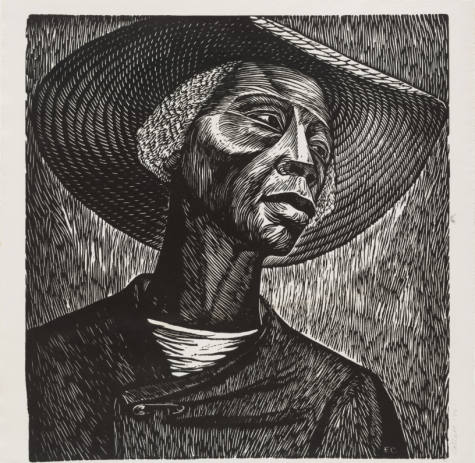

One of Elizabeth Catlett’s most notable works, Sharecropper, truly shows the purpose of her work, which she said was to “present black people in their beauty and dignity for ourselves and others to enjoy”, and could not ring truer than in this piece. Similar to the other pieces showcased, this printed art calls attention to the adversity of tenant farming in the form of a portrait. While I am incredibly drawn to the detail and style behind this piece, I am also drawn to the power given to the anonymous woman illustrated in her dynamic stance. Catlett was an artist highly driven to show social or political messages in her art, not only aesthetic, and focused greatly on the experiences of women. Though she only died in 2012, Catlett was the grandchild of two freed slaves, her grandmother telling her stories about the capture of her people in Africa and the suffering of working on a plantation, and she was the daughter of a single mother.

Faith Ringgold was born in Harlem in 1930, inheriting a deeply creative mind from her parents, the descendants of working-class families in the Great Migration. Her art, like the piece here, was inspired greatly by the people she interacted with and the culture as well as oppression she experienced. The numerous paintings in her American People Series showed how everyone was affected by the violence of race relations particularly in the 1960s, where decades of racial, economic, and political factors led to the inner city poverty suffered by many black citizens. The universal splattering of the blood across every individual — regardless of race, gender, or age — shows the struggle that no one could escape, the two children clutching each other showing fear for the future as the battle surrounds them. On my first seeing this piece, I was reminded of the 1937 Picasso painting Guernica, which also illustrated a time of fear after the bombing of the town during World War II, a painting that heavily inspired Ringgold and her approach to contemporary violence as a subject in her art. It is potent and memorable, like the print of Guernica in the Chamblee library that I pass every day.

As I look back on my time as a student here, I feel so grateful for the experiences I’ve had in this class and others that have opened my eyes to a world so frequently neglected in history and the present day. And as a young, white female I know I will never fully understand the experiences of the black community and have a lot to learn about so many cultures to truly gain an appreciation for them. But I hope that with continued exposure to all the forms of art and by sharing and hearing untold stories, the continued ignorance of such amazing artists and people can be lifted.

Most of my research and the pieces for this editorial were found using the Museum of Modern Art’s website, found here.