That’s It? Yes, Sometimes It Is

Goodbye, Chamblee.

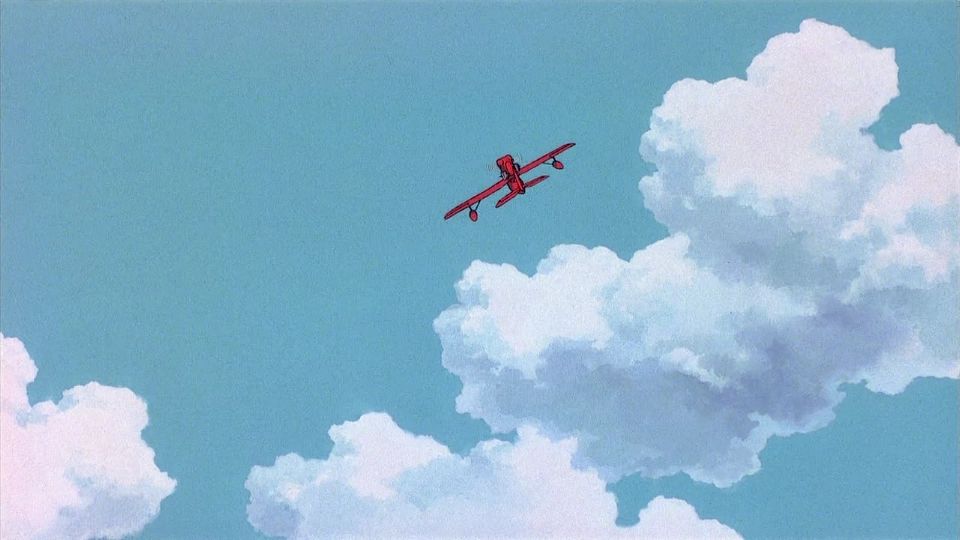

Photo courtesy of Studio Ghibli.

A screencap of Hayao Miyazaki’s “Porco Rosso” by Studio Ghibli.

May 6, 2021

To put it simply, Porco Rosso is Studio Ghibli’s best. Not because it’s about a kickass anthropomorphic pig who flies a tiny red plane and fights air pirates over the Adriatic Sea. Not for its meditation on political turmoil, disillusionment, and reconciliation. Not for its animation, feminism, chaos or charm. No—Porco Rosso is the best because for a movie so campy and fanciful, it sticks its landing calmly, realistically, and without drama.

I love a good ‘That’s it’ ending: they’re found, often, in obscure German movies, like In den Gängen, which ends with the protagonist remarking on how the forklift at his supermarket-workplace sounds like the ocean. Or, in a more mainstream example, the Coen Brothers’ True Grit, where Mattie Ross searches for the bounty hunter who saved her life thirty years ago—only to discover he has died, just a few days earlier. All are unsatisfying enough, inconclusive enough, and, for some bizarre reason, capable enough to compel. Deeply.

There is a distinctly western desire in cinema to produce stories with neat, deliberate conclusions. Incidentally, this extends to the college process: Common App and supplemental essays implicitly ask that you spin narratives from (what I imagine for most people are) subdued, smaller-scale experiences that might not be so coherent or transformative at first glance.

By January, I was totally burnt out from extrapolating lessons learned from the same Top Three Most Memorable Experiences of My Life. So, in a tiny act of rebellion, I fixated on the following quotation from the final installment of our “2020 Visions” series:

“I think that 2020 has taught me that…it’s, um…bro, I haven’t learned anything. I’m gonna be straight with you here. I have learned nothing this year. This has been a lost year for me.”

In an evasive response to an impossible question, our interviewee captured the entirety of an anticlimactic senior year. Looking back, I had an almost celebratory ‘introvert response’ to the first shelter-in-place order. But in a change of heart, I experienced bouts of nostalgia for vinyl school bus seats, powder pink cookies sold at under-skybridge bake sales, and our AP German exam proctor devouring her Publix sandwich during the 2019 listening comprehension section.

Then, with very little closure, junior year ran into senior year, and senior year, which was supposed to culminate at a college decision, turned into assignment, after assignment, after assignment, where everything was the most important thing in its allotted time period and where everything, in turn, lost its permanence behind faceless, gridded classrooms—until I realized that yes, I did miss Chamblee, its teachers, and being surrounded by the people who always surrounded me.

In truth, ambivalence followed me throughout high school: I was either tired because I was stressed, or stressed because I was tired. The goal, as it was soon realized, was to get in and out as quickly as possible, fueled by a promise that self-fulfillment would come at a great, big, shiny college—elsewhere. But I discovered a niche, in journalism and art. I found genuine excitement when analyzing literature. I was often comforted by the vitality of our cafeteria, and moved by the dedication of teachers and friends. I learned to volunteer, write polite emails, and to speak with others sans inhibition. And I anticipated that I would feel more prepared to say goodbye.

The realization slowly dawns that I may be coming out of a pandemic regressed, stunted, and not having yet comprehended the proximity of graduation. I’ll likely be entering college, mentally, still as a high school junior, followed by impending feelings of apprehension and anxiety. I’m excited to leave, yet uncertain about most everything that lies ahead—the exception is knowing that it’ll take some effort to get reacclimated.

So, how exactly do you go about an ending like this?

Well, Porco Rosso, in its intimate portrayal of aerial bounty hunting, Jazz-Age Italy, and survivor’s guilt, concludes in a similarly impermeable haze. Ultimately, we are denied insight into our title character’s whereabouts, his post-narrative aspirations and relationships. Does Porco turn back into a human? Will he pursue a life with Gina? Who knows.

Instead, the film chooses to assure us—with resounding, resolute conviction—that in the end, he is okay.