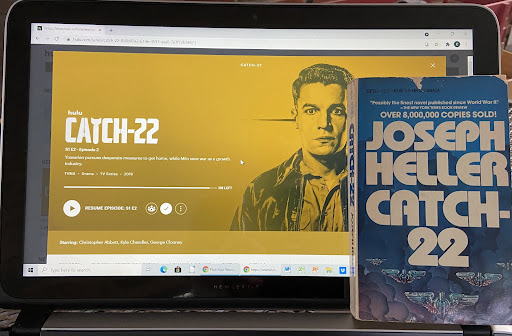

“Catch-22,” “Catch-22,” and Why Not All Books Should Be Adapted

Books have been being adapted into movies since film gained prominence in the early 20th century, but as streaming services become increasingly popular, even more novels can get even more faithful adaptations as limited series, which give filmmakers a greater runtime to adapt a greater portion of the source material. But what books should get adaptations? Novels are composed of a fundamentally different set of mechanics than film, and they can’t always be translated to the screen without sacrificing style, themes, or just the stuff that makes that book compelling.

Hulu’s “Catch-22” is a perfect example of this failure to translate the greatness of a novel into an equally interesting series. It isn’t actually very bad, let me first say that. It’s generally well-made, has some good performances, and there are still some excellent sequences in cramped bombers that are incredibly affecting and visceral. If I hadn’t read the book and loved it so much, maybe I wouldn’t be so critical of the show. However, I think the way the show is told (and how it ends) undercuts what makes Joseph Heller’s book so great.

The first thing you must understand about “Catch-22” the book is that it is told almost entirely out of chronological order. It frequently jumps from anecdote to anecdote regarding Yossarian and the other officers at the Pianosa air force base during World War II, with each chapter usually tied together by some character and what themes they represent. When a story is told in the book, its time period can only be determined through its relationship to other events in the story, and those events are sometimes only elaborated upon later. For example, the reader is told of the time that Milo, the mess officer at the Pianosa base, bombs the Pianosa base itself hundreds of pages before that event is elaborated on.

The book, then, is endlessly self-referential, with the reader understanding more about events that they had heard about before, because only later do they understand the motivations of the characters at that point in the story and the developments that led to any single event. It also allows the novel to build organically, with the topic of the different stories becoming darker and darker as the book continues. The characters around Yossarian were actually dying all the time, but the way the book tells it, we only get to know the grisly details deeper into the story. Most of the comedy in the book, too, is lighter in the early sections and gets darker as the pages turn. After the book has completed its transition into the darkness, there is a pivotal scene as Yossarian walks through Rome at night, realizing as he does that he is becoming more and more alone as time passes and his friends die. This is where the gravity of all that had happened in the story so far, much of being previously told comedically, hits the reader.

The Hulu show, however, is told entirely chronologically, with some brief flashbacks that are clearly delineated. This shows the limitations of the medium; the filmmakers effectively couldn’t have told the story out of order, as it would be too confusing for any audience to follow in the form of a show, and there is no narrator to note the changes (yes, there could have been an ever-present narrator, but that’s usually lazy and ineffective for films anyway, especially ones based on books). The first downside of this straightforwardness is simply that there are no satisfying “aha” moments like there are in the book, where the reader can finally put together a set of events that had been previously referenced. Also, because the story is chronological, we get the more depressing events distributed across the six episodes perhaps not entirely evenly, but far more so than the novel. This means that when the show recreates the scene in Rome that was so affecting in the original, it doesn’t feel so impactful. The show was always dramatic and grim.

This is another, perhaps more subjective issue, but the show also doesn’t lean far enough into the deadpan humor of its source material. The book is legitimately clever and funny throughout, but the show cuts a lot of that comedy in favor of a more dramatic tone. I think this change can be illustrated by two characters, Yossarian himself and Chief White Halfoat. Yossarian in each medium has the same basic traits and motivations, but the extremes to which he takes his agenda varies. In the book, Yossarian is outwardly selfish, disagreeable, and hilariously paranoid. He isn’t necessarily a terrible person, but it is made clear that while Yossarian sees himself as the only sane one on the base, he is wrong; there is no one sane on the base. In the show, though, Yossarian is far more reasonable and sympathetic, to the point that he can be boring, at least compared to who he is in the book. He completes many of the same actions in both mediums, but he seems so much less frantic and careless in these actions in the show that he comes across completely different.

When he does something out of the ordinary, like when he accepts a medal from General Dreedle without any clothes on, it doesn’t seem funny in the show like it does in the book, especially when it is mentioned in passing before the entire situation is elaborated on later in the novel. Chief White Halfoat also shows the line between comedy and drama, as he does little for the story’s plot, so he is omitted entirely from the show. This is a shame, because he’s probably my favorite character in the book, but he just doesn’t fit the tone and style of the Hulu adaptation. In remembrance of him (in the novel, he dies of pneumonia, which he had been wishing for), here is maybe the best excerpt from the book:

Captain Flume was obsessed with the idea that Chief White Halfoat would tiptoe up to his cot one night when he was sound asleep and slit his throat open for him from ear to ear. Captain Flume had obtained this idea from Chief White Halfoat himself, who did tiptoe up to his cot one night as he was dozing off, to hiss portentously that one night when he, Captain Flume, was sound asleep he, Chief White Halfoat, was going to slit his throat open for him from ear to ear. Captain Flume turned to ice, his eyes, flung open wide, staring directly up into Chief White Halfoat’s, glinting drunkenly only inches away.

“Why?” Captain Flume managed to croak finally.

“Why not?” was Chief White Halfoat’s answer. (Heller, 1961, p. 58)

This scene, with really no importance to the overall story, could never have made it into the Hulu adaptation, but it, and other short comedic vignettes, are a huge part of what makes Heller’s “Catch-22” so captivating.

My third main problem builds upon my first, and it is the ending of the story. In the book, the book ends on somewhat of a hopeful note, with Yossarian finally deciding to desert the air force like his former roommate Orr, who had managed to fake his death and escape to Sweden (on a separate note, the always-earnest Orr fit very well into the Hulu show and was survived the adaptation better than perhaps any other character besides Milo, who was also portrayed well). This decision is good for Yossarian, and shows that he is finally doing something himself to get out of the military, not just letting someone else discharge him, as he had had an offer to go home in exchange for offering a good word on his commanding officers. He is happy, and the reader should be happy that he is escaping the fate that befell many of the rest of the novel’s characters and doing it his own way.

In the show, however, Yossarian is still flying his missions, even after almost everyone he knew at Pianosa is dead or has gone home. It’s a somber ending, and not one the show needed. It is even mentioned that Orr was alive and did escape. Yossarian knows that, but he is still resigned to his fate. It’s depressing, and just makes the whole show seem a bit pointless, as we had been waiting for Yossarian’s discharge since episode one. Maybe the show is making a cynical point on the lack of ability people have to challenge authority today, but coming to that conclusion after showing hours of rebellious attempts to challenge that authority feels completely unsatisfying. I said at the top of this paragraph that this issue related to my first problem, and that is because these two endings hinge directly on when a very significant event in the plot happens chronologically.

In both stories, Snowden, a young gunner, is shot and killed in a plane on a mission. Yossarian holds him as he bleeds out, trying to comfort him as he dies. This is also something that is related to the reader near the end of both the show and the book. It is so formative in the conclusion of the story that clearly the filmmakers thought that they couldn’t allow it to take place when it did chronologically in the book, which is about midway through the story. Instead, it is placed at the very end of the series. The filmmakers changed Yossarian’s reaction to the event as well. In the book, Snowden’s death led to Yossarian’s feverish commitment to self-preservation, which was a heightening of his existing reluctance in putting his life on the line over and over again. In the show, that reluctance is never truly heightened, and when Snowden finally dies, it just breaks Yossarian, leading to the somber resolution mentioned earlier.

I don’t want all of this to give the wrong impression; I think book adaptations can be great, and this show was pretty alright on the whole, but filmmakers need to be more discriminate both in what they adapt and how they adapt it to preserve the greatness of the source material. Hulu’s “Catch-22” isn’t so bad, but why does it exist when I can just read the book?

Your donation will support the student journalists of Chamblee High School Blue & Gold. Your contribution will allow us to print editions of our work and cover our annual website hosting costs. Currently, we are working to fund a Halloween satire edition.

Thomas Rice is a senior, and this is his second year on the staff. In five years he hopes to be celebrating a Hawks NBA Finals victory after graduating college. The movie that would best encapsulate his Chamblee experience is "Tall Girl", except instead of “Girl” it’s “Boy” and instead of being about himself it’s about Blue & Gold staff writer Adam Pohl.