It seems there’s always a conflict in the popular mind between the old classics and new favorites when it comes to books. Whatever your side is, there’s ample choices; even the most dedicated reader is unlikely to run out of either the tried and true or new and shiny. Discourse has intensified even further in recent times over what some readers say is a new, harmful wave of literature originating from TikTok—or as the app’s reading community calls it, BookTok—that lacks quality, is produced in a rapid-fire fashion similar to highly criticized, consumerist micro-trends in fashion, and centers primarily around two-dimensional tropes that have never received as much success or publishing to date.

Despite the ample criticisms of the revolving door of BookTok, it has undoubtedly brought a new love of reading to teens and young adults in particular. Many of these newly-devout readers are adamant about the quality of their favorite books. Videos proclaiming the newest trendy romance as “sure to be a classic in thirty years” are abound, with each displaying a different roster of books and tropes (that somehow still manage to look almost identical). Although the past twenty years has unquestionably produced several literary superstars and a litany of good titles alongside them, I believe that literature (at least in comparison to its current state) may have passed its better days in the past century. Here are three case studies:

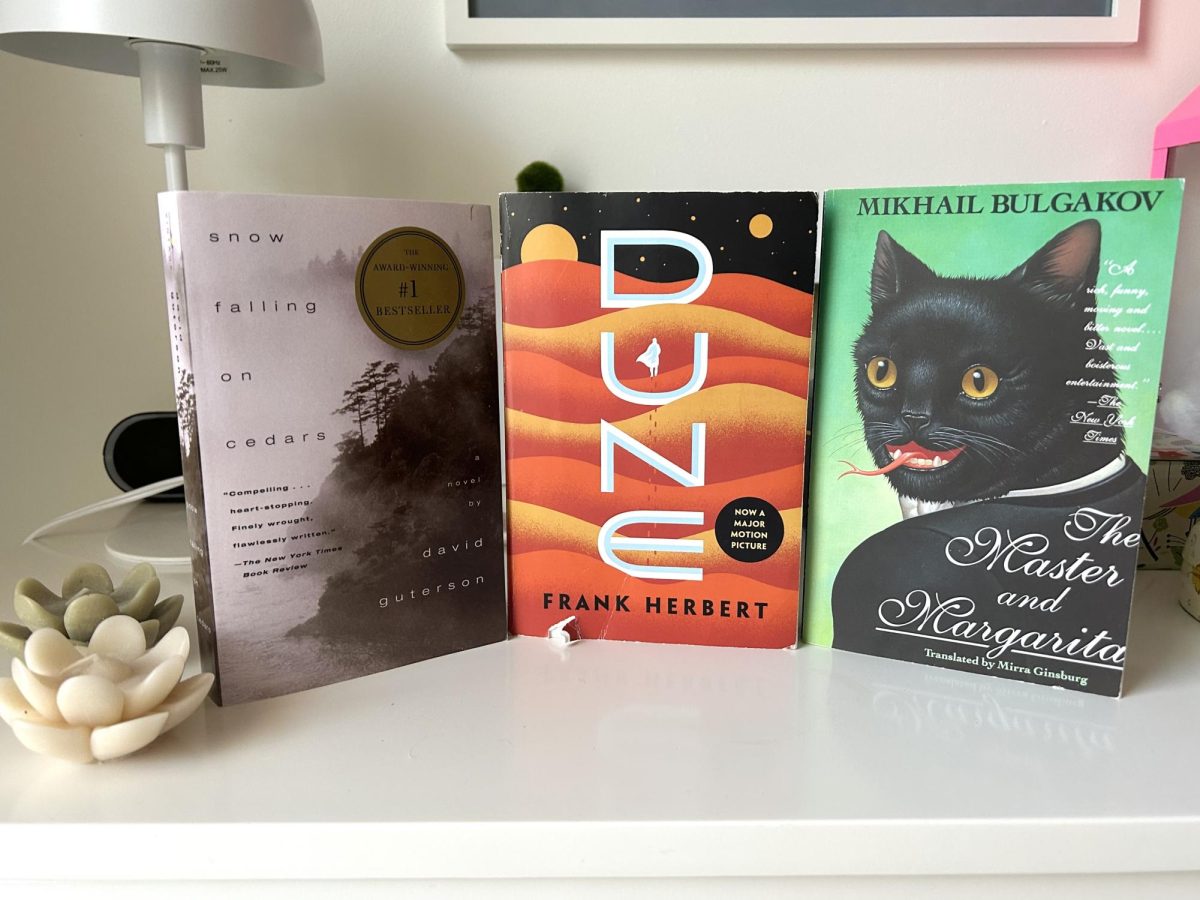

Dune (1965), Frank Herbert

Dune faces no question as one of the literary greats and perhaps the defining piece in sci-fi. Despite being published almost eighty years ago, the modern reader can find invaluable wisdom in its some 600 pages. The shockingly modern core of the book, the tale the people of desert plane Dune and the inconceivable sacrifices they make to give their planet a hope of life in a future they will never see, is accompanied by the engrossing tale of the royal Atreides family (which also creates a good juxtaposition between the story’s moral and entertainment). Herbert’s ability to create a fictional world is remarkable and incredibly enjoyable for the readers of the Dune saga: he effortlessly creates distinct and interesting people and families that interact with each other realistically and a universe tied together by fictional adaptations of Christianity and, more prominent in the book’s setting, Islam. Like almost any sci-fi book, the first read can be confusing and even tedious, but mass-market copies have a helpful dictionary and the core story is enjoyable regardless.

Snow Falling On Cedars (1994), David Guterson

Like Dune, Snow Falling On Cedars was lucky enough to receive ample appreciation in its time, but I feel that it’s underappreciated by many due to its lack of the novelty that seems to be the key in producing bestsellers today. Snow Falling On Cedars examines the story of two Japanese families living in a primarily white fishing community off Puget Sound in the aftermath of World War II and Japanese internment camps. The story initially centers around Kabuo Miyamoto, a fisherman accused of killing the white Carl Heine, but eventually snakes into the past, revealing a web of connections between Miyamoto’s wife and local reporter Ishmael Chambers as well as the generations-long dispute involving a plot of land purchased by the Miyamotos from the Heines and then lost when they were forced to Manzanar, an infamous internment camp. Snow Falling On Cedars is astute and real—its characters frequently make bad decisions, sometimes even infuriating ones, but it’s these missed opportunities and moments of hesitation that lend the book’s cast humility and lead the discussion of how WWII shook one small community to a breathtaking depth. To me, this is what many modern books lack: its characters are human and make mistakes that are stupid and yet undoable. This irrevocable chain of cause and effect is what makes the book so real and captivating; though it has a deep rooting in the past, the book is and will be for probably as long as humans are around.

The Master and Margarita (1967), Mikhail Bulgakov

The Master and Margarita was written in the 1940s but, courtesy of Russia’s Soviet rule interpreting its uniqueness negatively, didn’t see light until almost thirty years later. Crucial to the book’s rejection under the regime and the wide acclaim it’s met since is the strong themes of religion throughout the book. It tells two parallel tales of Pontius Pilate in ancient Rome and Satan and his retinue arriving to wreak havoc in Moscow in the 1940s. The book is incredibly dense and at times confusing: in classic Russian lit style, each character has a minimum of three names, making the plot sometimes near impossible to follow without some kind of family tree on hand. But its dry satire lends it enjoyability while also offering insight to the unique, bygone culture that once existed in the Soviet Union. Although I wouldn’t recommend this book to most on behalf of its heft and density, for a reader looking for a more culturally insightful and creative read, it’s a great match.