Women in STEM Blazing New Trails: Dr. Sarah Trebat-Leder

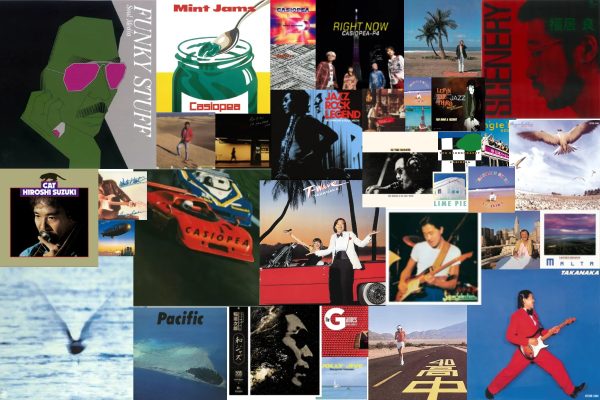

Photo courtesy of Emory News Center 2014.

Dr. Sarah Trebat-Leder in her first year of Emory Math Circle.

There is a growing phenomenon in Atlanta, and it started at Emory. Hundreds of students visit Emory University every weekend to attend Emory Math Circle, taking part in fun, accessible, and engaging lessons on topics from game theory to permutations to puzzles. It’s a place where students can see the creativity of math in a collaborative environment and answer exciting questions, like whether you can always beat your opponent in Connect Four. The program has had a tremendous impact on the students of Atlanta, opening their eyes to entirely new worlds.

The founder of the program, Dr. Sarah Trebat-Leder, was a graduate student at Emory when she started the club in 2014. She is an advocate for math circles, which expose middle and high schoolers to creative mathematics, and women in STEM.

Trebat-Leder was an undergraduate student at Princeton where she served as the president of the math club and helped to run PuMAC (Princeton University Mathematics Competition), one of the most well-known national math competitions, before moving to Atlanta. While at Emory, she worked on cutting-edge research in number theory, specifically an area known as moonshine. She now lives in San Diego, California, and is the Chief Personnel Officer at Art of Problem Solving, a company that works to promote math and math competitions to hundreds of students throughout the country.

Trebat-Leder began Emory Math Circle to foster a collaborative environment for kids from around Atlanta.

“Kids get to come every weekend and do math in a setting that’s not a competition where they learn all these cool, new, different things in math that [they] don’t normally see at school,” said Trebat-Leder. “[They] get to meet other kids that are also really interested in math.”

She realized the importance of community while she was in high school. She enjoyed the American Regions Mathematics League (ARML), a national competition that brings students from one (or several) states together into a team.

“When I was in high school, it was really important to me to have communities of other people who really liked math, so going to a math summer camp or being on an ARML team was somewhere where I felt like I fit in more,” said Trebat-Leder.

She was inspired to start a math circle at Emory because of her experiences at Princeton.

“I had helped out with a math circle when I was at Princeton. I had never heard of math circles before I was in college, and I thought it was a really cool idea,” said Trebat-Leder. “When I started grad school, I immediately knew that I wanted to start a math circle. I had started working on it the fall of my first year and we had our first classes in January of my first year.”

Trebat-Leder also translated skills she learned at Princeton into Emory Math Circle.

“I also knew that I really enjoyed running programs and organizing things,” said Trebat-Leder. “In college, I was the president of the math club and I had spent a lot of time helping to run PuMAC, a math competition that’s run by Princeton undergraduate students, so I really enjoyed doing that kind of work: doing things in math, but doing the planning, organizing, logistical side of them, not just the teaching side of them.”

Long before she arrived at Emory, Trebat-Leder was in middle school. It was at this age when she first discovered her love of math.

“At the end of the sixth-grade year, we took a test and the people who did well on it got placed into eighth-grade math in seventh grade. In eighth grade, the group of us that were a year ahead […] had our own little math class,” said Trebat-Leder. “I think that was the first time that I thought of math as something that I was good at and that I really enjoyed.”

In high school, Trebat-Leder took advantage of many opportunities. She was selected for the Lehigh Valley ARML Team as one of the top students from New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware, and competed with the team in the national competition. She also participated in a summer program at Hampshire College in Massachusetts.

“In high school, I did ARML for three years, 10th grade through 12th grade, and then after 10th grade, I went to Hampshire College Summer Studies in Math (HCSSiM), a summer camp in Massachusetts, and that was where I really fell love in math,” said Trebat-Leder. “It was the best thing ever. We were doing eight hours of math every day for six weeks, and it was amazing.”

At HCSSiM, Trebat-Leder discovered her future career path.

“That was when I [realized] this is what I want to do with life,” said Trebat-Leder. “I decided that summer, I wanted to be a math professor, I wanted to major in math, I wanted to get a PhD.”

Trebat-Leder also enjoyed reading books about math and theoretical physics during high school.

“At that age, I really loved reading those books, popular books about string theory and theoretical physics,” said Trebat-Leder. “Brian Greene had written The Elegant Universe, and that was one of my favorite books when I was in eighth or ninth grade.”

Being an underrepresented group in math has not been without its difficulties. While going through some old photos, Trebat-Leder recently discovered the gender imbalance in her ARML team.

“The Lehigh Valley ARML Team had four teams that were part of it. The top team was the one that was competitive to win nationally, and that team was all guys,” said Trebat-Leder. “I was the captain of the second team and I was the only girl on that team.”

What was important for Trebat-Leder was that there were some other girls.

“There were a few girls on the third and the fourth team, and so I was thinking about that [and how] I didn’t really remember that there were so few girls,” said Trebat-Leder. “What was important to me was […] that there were a few other girls who were on the team at all, and so it was still a really good social experience for me.”

As a result, Trebat-Leder felt less isolated.

“Mainly, at that age, I was hanging out with the other girls on the team but I still had a few people to hang out with,” said Trebat-Leder. “Even if it was mostly guys, it didn’t really bother me. I think, if I had really been the only one on the Lehigh Valley Team, that would have felt much more isolating but because there were a few other girls, it was okay.”

When Trebat-Leder was accepted into Emory’s REU (Research Experiences for Undergraduates) program, she was also confronted by the gender imbalance.

“This was how I first came to Emory […] was through the research program [REU], and it’s a super competitive program,” said Trebat-Leder. “I remember there were a bunch of women participating, and I just remember feeling like I had only gotten in because I was a woman. It was so competitive that it seemed obvious that the competition was way stiffer to get into that program as a guy, and so that made me more self-conscious and kind of worried about [if I was] contributing enough to our team and [whether] I really deserved to be there.”

Trebat-Leder went on to overcome these obstacles and do incredible research through REU. Her experiences at Emory through this summer program led her to apply to Emory for graduate school to gain her PhD.

Today, at Art of Problem Solving, she is translating her math skills into an unexpected position.

“[Being the Chief Personnel Officer] is kind of an unexpected job to have, coming from math,” said Trebat-Leder. “I spend a lot of time reading laws, learning the details of California’s sexual harassment prevention […] and how overtime works in different states and understanding all these little details of employee-focused laws, which is something that I would not ever have expected myself to be doing, but it is actually very mathy because you have to translate what’s written into an actual algorithm […] so we can program it into our systems.”

Trebat-Leder’s experience in the math world also helps her with hiring employees for the company.

“The other stuff that I do a lot of is hiring, so working with whoever is going to hire someone to figure out what are they looking for,” said Trebat-Leder. “I’m not using math in an explicit way. I’m not teaching or writing curriculums, but it helps a lot when you’re trying to hire people who have backgrounds in math to be able to understand what they’re doing and their resumes and also just to understand what everyone’s doing in different parts of the company.”

Due to her success, Trebat-Leder serves as a role model for many students. She believes that high schoolers can benefit immensely by delving into their passions.

“I think I’m generally a proponent of seeking out the things that you’re passionate about […] and [not worrying] as much about how they’re going to connect to a future career or to each other,” said Trebat-Leder. “I think that when I was in high school, I was doing all these different things that I really enjoyed, and I definitely recommend participating and seeking out enrichment activities and things that you’re excited about.”

Trebat-Leder also gives some specific examples.

“If it’s a math circle or a summer camp or if someone really enjoys and thrives off of doing math competitions… But it could also be first robotics team or it could be science olympiad,” said Trebat-Leder. “Just finding the things that you really enjoy and that challenge you and that you’re doing because you generally want to and not just because of getting into a good college or preparing yourself for a career. I think that doing that makes you more attractive to colleges and also prepares you for the career that’s going to be right for you.”

Trebat-Leder advises girls to seek out other girls that share their passions.

“If there’s something that you’re excited about that there aren’t a lot of girls in, try to find at least a few other girls that are also excited about that,” said Trebat-Leder. “There’s a big difference between the only one and being a few girls, having a group.”

Trebat-Leder also stresses the difference between math competitions, which can be discouraging if not approached with the right mindset and the more collaborative world of research math. Trebat-Leder wants girls to know that success does not necessarily correlate with the competition world.

“Don’t be discouraged if you don’t like math competitions,” said Trebat-Leder. “Math research is super different than math competitions and being good at or not good at or enjoying or not enjoying math competitions doesn’t really correlate with being good at math in general. Math is not about speed, not about being able to solve something on the spot under time pressure, [and] not about memorizing things. Most mathematicians spend years working on a single research problem. That’s one big message, not just to girls, but I think especially to girls.”

Thinking about the nature of these competitions can lead to some important questions.

“If there are math competitions where the winners always end up being boys, thinking about why that is the case [can be important],” said Trebat-Leder. “What are the competitions actually testing for? What are they selecting for? Is that actually what we want them to be selecting for? Are there other kinds of skills that we should be celebrating more?”

Trebat-Leder believes that society can do more to show girls the creative aspects of math.

“I think that we don’t show people very much that math is a creative, collaborate endeavor, and I think that a lot more people in general, but also a lot more girls, would be excited about it if they saw what math really is like,” said Trebat-Leder.

Trebat-Leder sees the solutions in offering students a different kind of opportunities.

“I think that we should be giving students the experiences to discover and create math for themselves, to ask their own questions, to look for patterns and come up with conjectures… to do that process of mathematics,” said Trebat-Leder. “There’s no reason that you can’t do that even with an elementary schooler. I think, actually, younger kids are natural mathematicians. They’re curious and ask tons of questions and can have an amazing imagination, and I think that we need to preserve that in students as they get older and keep nurturing that.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Chamblee High School Blue & Gold. Your contribution will allow us to print editions of our work and cover our annual website hosting costs. Currently, we are working to fund a Halloween satire edition.

Catherine Cossaboom is a senior and editor of the Blue & Gold. In her free time, you can find her solving way too many math problems, going on wandering walks to make friends with the deer in her neighborhood, and training her kittens to compete at the next Kentucky Derby. In five years, she hopes to be traveling across the country, running math circles, writing columns, and turning math into a performance art to empower girls to take on the world's problems. This is her third year on the staff.