Controversial House Bill 888 Would Affect Teaching About Race in Schools

A recent bill before the Georgia House of Representatives, House Bill 888, has created controversy among politicians, educators, and students alike. The bill, which critics say would limit how race is discussed and taught in schools, is part of a wave of Republican-backed bills across the U.S. concerning critical race theory in schools.

The bill, captioned “Education; treatment of race and other individual traits and beliefs; add new statutes and amend various existing statutes” was introduced to the Georgia House of Representatives last month by Republican state representative Brad Thomas and is currently before the House Committee on Education. Additional sponsors of the bill include Rick Jasperse, Will Wade, John Carson, Alan Powell, and Martin Momtahan (all of whom are also Republicans).

What the bill does

The eighteen-page bill includes a variety of provisions, ranging from prohibiting curriculum that could be considered racially discriminatory to prohibiting teaching that “the United States is a systemically racist country.”

Critics say the bill limits how race is taught in schools, while proponents say the bill is needed to prevent teachers teaching elements of critical race theory in schools.

The full text of the bill can be read here, on the Georgia General Assembly website.

Student opinions

All students interviewed by The Blue & Gold were opposed to House Bill 888, although the majority of students at Chamblee are unfamiliar with educational legislation in the Georgia General Assembly.

The bill begins by stating that the Georgia General Assembly establishes that “Slavery, racial discrimination under the law, and racism in general are so inconsistent with the founding principles of the United States that Americans fought a civil war to eliminate the first, waged long-standing political campaigns to eradicate the second, and rendered the third unacceptable in the court of public opinion, all of which dispels the idea that the United States and its institutions are systemically racist and confutes the notion that slavery, racial discrimination under the law, and racism should be at the center of public elementary, secondary, and postsecondary educational institutions.”

Senior Eli Scruggs (‘22) found this passage contradictory based on the actions of the Founding Fathers of the U.S.

“[The bill includes] how the United States was founded and perpetuated on the principle of equality. And they talked about how basically they wanted to emphasize that the United States is not racist, which is laughable to me considering the Founding Fathers themselves owned slaves,” said Scruggs.

Freshman Eitan Heled (‘25) believes that education should objectively include all parts of history.

“My general opinion is that schools are a place for education and we should be teaching about anything regardless of what somebody thinks, we should be teaching about everything, and we should be teaching about the plausibility of everything,” said Heled. “And so I think that largely House Bill 888 is a political power move, I think that it has very little real substance, and I think it’s fundamentally flawed.”

One of the provisions of the bill would prohibit teaching that “the United States is a systemically racist country,” which Heled and other students disagreed with.

“I think that an attempt to stifle discussion about [systemic racism] is […] wrong, because we should be having discussions about groups that are oppressed, we should be having discussions about groups that have privilege, regardless of what anybody thinks,” said Heled. “We know that Jim Crow laws existed. We know that slavery existed. And there isn’t just an eraser that we can use to clean the slate. Racism does exist, it has existed, and it will continue to exist, unless we continue teaching about topics like these, and we promote inclusivity.”

Scruggs mentions that one of the books read in his multicultural literature class related to the content of the bill.

“Right now we’re reading […] ‘How to Be an Antiracist,’ which explicitly comments on the United States’s past racist policies. One of the specific things that the bill banned the teaching of is that the United States is […] systemically racist,” said Scruggs. “It went through all these things and it [included] you can’t teach one race is above another, entitled to anything else, should feel guilt for anything that other members of the race have done. […] If the United States was not systemically racist, why would you ban teaching that?”

Senior Mia Wood (‘22) accepts that it’s okay to be uncomfortable learning information in school for the sake of understanding what others have experienced.

“I think in general, we kind of have to live with being uncomfortable sometimes. And I mean, we can’t just be content being ignorant,” said Wood. “The problem of racism in general and discrimination in this country can’t really be solved unless people realize that sometimes what’s been ingrained in them for so long isn’t correct, and how their actions affect other people.”

Junior Demetrius Daniel (‘23) maintains the opinion that withholding true parts of history limits students’ knowledge.

“I think that not enabling these types of discussions in parts of our society as a whole is limiting our society’s education. […] I’ve seen things like critical race theory where people don’t want to talk about race, or the holocaust, but these are tragic events that occured in our time, and we need to talk about them even if it might make some people uncomfortable or offend people,” said Daniel. “If we don’t teach the next generation about our issues, growth will probably never happen.”

Teacher opinions

Two of Chamblee’s English teachers — Kimberly Nesbitt (who teaches AP English Literature and Composition and world literature) and Adrienne Keathley (who teaches multicultural literature) are opposed to House Bill 888. Both teachers feel that the bill would be detrimental to the education of students in Georgia.

“In summary, I think it would be a shame to deny a full picture of history in a place of learning,” said Keathley.

Keathley feels that the bill conveys a sugar coated facade of history.

“I would argue that we’ve been presented with a romanticized version of specifically American history forever,” said Keathley. “I don’t think that’s something that if it isn’t broken, don’t try to fix it kind of scenario. It very much has been broken, and very much has been excluding the majority, at this point, of people and their family’s legacies experiences throughout history.”

Nesbitt believes that the bill is a political viewpoint that shouldn’t have a bearing on education.

“From my knowledge, it’s a very long document. […] And somewhere buried in there with all the other stuff for teachers K-12 is the fact that they are opposing critical race theory to be taught,” said Nesbitt. “It seems to be a political viewpoint. [It] is not political. It’s an educational viewpoint. And I don’t think that the government should have any say in what happens in a classroom, because it’s not directly affected by anything that’s political.”

Since students may not have previously been taught about these topics, Nesbitt points out bills like this may also encourage students to learn about topics such as critical race theory and systemic racism.

“The laughable part about all of that is by them bringing it to the forefront, now students want to learn these things. Whereas, it really wasn’t being taught in K-12. That was kind of a hierarchy as far as when they went to college, if you were in law, if you were taking a specific studies class for literature, or psychology, or sociology, then they would teach from the lens of critical race,” said Nesbitt. “You could see how systems were put in place or how to look at literature differently once you get to those points, especially if you’re in ethnic studies and so forth. […] What they’ve done now is that they’ve created a space where your generation wants to know more about it, because they’ve made it a problem.”

Nesbitt reiterates that not talking about an issue doesn’t mean that the issue doesn’t exist.

“The biggest thing is that the fear, and the misconceptions, and truth, is that by not talking about it, they think that it’s not an issue. And by talking about it, it actually helps create those conversations where you can get rid of narratives that are not true. I think Ruth Bader Ginsburg, in one of the articles [I gave my class], said that, ‘You can’t address a racial issue without talking about race.’”

Keathley also believes that issues like House Bill 888 discourage people from becoming teachers.

“It’s not the only, but it is one more reason that our teachers are leaving in droves. We cannot keep young teachers more than five years, and this isn’t helping, the lack of respect and autonomy that teachers are receiving through bills like this,” said Keathley. “Why would anybody want to go into debt for multiple degrees in a profession where you are still treated like a child and not an adult, and told what you can and cannot teach? If you really want to look at it from a larger level, I think that it is a great threat to public school, period, not just in your history classes, because that will filter out and into every other discipline eventually.”

Views on the financial penalties

One element of House Bill 888 is financial penalties, with the state withholding money from school systems that violate provisions of the bill.

“The State Board of Education shall withhold 20 percent of the state contributed Quality Basic Education Program funds allotted to the local school system or public elementary or secondary school in accordance with the provisions of Code Section 20-2-243,” states the bill.

Critics of the bill have said this could drain hundreds of millions of dollars from public schools in Georgia.

Senior Oishee Akter (‘22) brought up concerns that this is contradictory with Governor Brian Kemp’s message of having fully funded schools.

“In a time when Governor Kemp said this is the first time we’re supposed to be fully funded schools in a really long time, I think House Bill 888 really is a contradictory bill to what he’s saying. In his State of the State speech, he said he would like to fully fund schools but he also said he would like to support bills like this,” said Akter. “When you’re taking funding away from schools that are trying to teach the true history of the United States.[…] think that’s taking away from what we really need to learn and what we deserve to learn, which is the truth.”

Other students brought up how many schools are already underfunded.

“I think it’s absolutely not fair. Schools are somewhat underfunded as is, and I think that, especially in lower income neighborhoods and districts, since income taxes largely pay for schools,” said Heled. “I think that generally, underfunding schools is not a good idea, and that’s pretty much it, it’s not a good idea.”

Scruggs asserts that cutting funds is impractical and tone-deaf.

“I think it’s ridiculous that they’re considering taking away 20% of a school’s funding just for someone teaching that the United States has a checkered past at the very least. And it’s like, it has to be willful ignorance, right, that they just want to believe in a United States that was what they were raised to believe it is instead of what it actually is. It’s insane that we have people like these who don’t know their country’s history or choose to ignore it making decisions for us,” said Scruggs.

Senior Brian Roberts (’22) described penalties as an effort to silence people through political power.

“It’s kind of outrageous. It’s literally like using monetary power just to silence people, which is kind of the heart of capitalism in a way. So I’m not surprised that we as a country are committing to this so strongly,” said Roberts. “But I would think, I don’t know, with all the old people in charge it kind of makes sense that they don’t want to talk about all of their sins so, that’s my opinion.”

Keathley brought up how the threat of financial penalties could cause people to be constantly worried about what they are saying, pointing out the existent issue of school funding.

“It’s certainly the way in which to force administration’s hands to put down the hammer, metaphorically speaking, and really looking at the lesson plans, coming into the classes, following up on, anonymous or otherwise, tips about conversations that could be happening, and I fear that it could create this McCarthyism ambiance,” said Keathley. “If people are constantly worried about what they’re saying and how they’re saying it and who their audience is, it really takes away from the intrigue and the inquiry of education. And I think that’s frightening for our future, and what better way to ensure that it falls in line than just to threaten to take away public funding, which is such a struggle anyway, for basic resources.”

Outside of Chamblee

Outside of Chamblee’s school walls, various school board members, advocacy groups, and politicians have expressed views of the bill.

The bill has seen support from conservative groups such as Heritage Action, the Manhattan Institute, and Protect Student Health Georgia, and seen opposition from groups such as the Southern Poverty Law Center Action Fund, the Intercultural Development Research Association, and the Georgia Youth Justice Coalition.

Akter spends some of her time working for the Georgia Youth Justice Coalition, engaging with other students about youth issues.

“The Georgia Youth Justice Coalition is a student run organization and we have a lot of engagement with youth surrounding legislation that’s currently going on and we try to uplift youth voices in regards to the [Georgia General Assembly],” said Akter. “Whether that be connecting students to their legislators, getting out social media posts, just educating, spreading the word about all of these bills and also giving students a voice.”

In January, fourteen members of the school boards of Cobb County, DeKalb County, Gwinnett County, Clayton County, and Atlanta Public Schools, signed a letter opposing House Bill 888.

Will the bill pass?

For a bill to pass through the Georgia General Assembly and become law, it has to go through a series of steps involving both legislative chambers (the Georgia House of Representatives and the Georgia Senate) and the governor:

Idea → Drafting → Introduction and First Reading → Second Reading → Committee Action → Third Reading and Passage → Transmittal to the Other Chamber → Governor’s Signature/Veto → Act

House Bill 888 is currently past the second reading stage and is currently before the House Committee on Education, awaiting committee action.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Chamblee High School Blue & Gold. Your contribution will allow us to print editions of our work and cover our annual website hosting costs. Currently, we are working to fund a Halloween satire edition.

Allison Lvovich is a senior, and this is her second year in journalism. In her spare time, she plays/teaches tennis and plays chess. In 5 years time, she sees herself doing something related to statistics. One movie that encapsulates her Chamblee experience is "Legally Blonde."

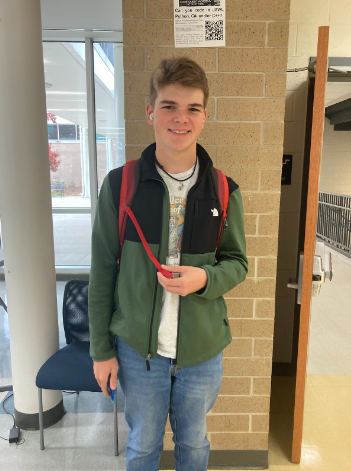

Keegan Brooks is a senior at Chamblee and this is his third year with The Blue & Gold. In five years, he hopes to be a student or alumni of a college somewhere. Hopefully by then he will have also finished the shows that he started watching, but never finished. He can be contacted via email at [email protected] or on Twitter @KeeganATL.